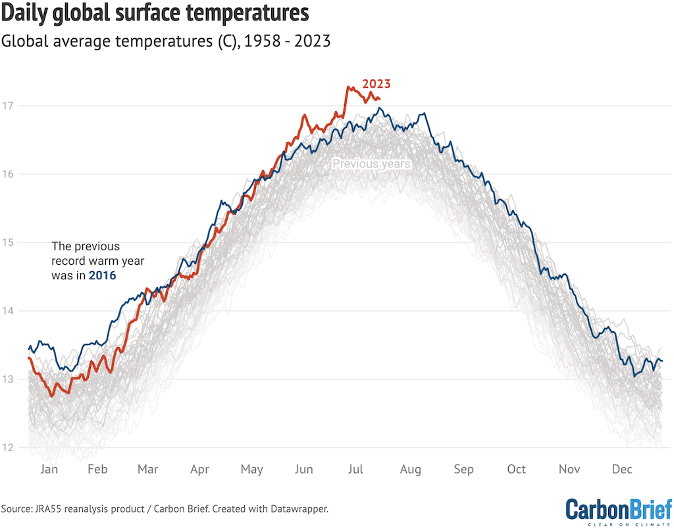

July 2023 might go down in history as the moment when humanity finally grasped the horrific consequences of our fossil-fuel addiction.

As we prepare to live in a scalding world with increasingly extreme weather events, it might be time to consider adaptations such as underground living.

Surrounded by masses of rock and soil that absorb and hold heat, temperatures can remain far more stable without a need to rely on energy-intensive air conditioning or heating.

Not only is it possible to live a life below, people (and animals!) have been living comfortably underground throughout history.

But is it a viable solution for dealing with an emerging climate crisis?

White man in a hole

In the opal-mining town Coober Pedy in South Australia, 60 percent of the population capitalizes on this effect by living underground.

The name Coober Pedy comes from an Aboriginal phrase, kupa piti, which means 'white man in a hole'.

Through the sizzling 52 °C (126 °F) summers, and freezing 2 °C (36 °F) winters, their 'dugouts' stay a consistent temperature of 23 °C (73 °F).

Without this natural rock shelter, summertime air conditioning would be prohibitively expensive for many.

Above ground, the summer heat can cause birds to fall out of the sky and electronics to fry. But, below ground, many residents have quite luxurious set-ups, with cozy lounge rooms, swimming pools and as much space as they care to carve out.

Homes must be at least 2.5 meters below the surface to prevent the roof collapsing. Despite this regulation, cave-ins do happen occasionally. In the 1960s and 70s, locals cut holes in the ground using pickaxes and explosives. Today, they use industrial excavation tools, although the work is sometimes still done by hand. Cutting out large chunks of rock doesn't take very long as the sandstone and siltstone is so soft that it can be scratched away with a penknife.

Sometimes home renovations even pull a profit; one man found an opal worth AU$1.5 million (US$980,000) when installing a shower.

Every so often, people will accidentally burrow into their neighbors' home. But, in general, going underground maximizes privacy.

The lost city of Derinkuyu

In 1963, an unnamed Türkiyen man took a sledgehammer to his basement wall during a renovation of his Cappadocian home. Finding his chickens kept disappearing through the hole, he investigated further and discovered a vast maze of underground tunnels. He'd found the lost city of Derinkuyu.

Built as early as 2000 BCE, the 18-story tunnel network reaches 76-meters below the surface, with 15,000 shafts to bring light and ventilation to the labyrinth of churches, stables, warehouses and homes which were constructed to house as many as 20,000 people.

It's thought that Derinkuyu was used almost continually for thousands of years as a shelter during wartime. But it was abandoned abruptly in the 1920s following the genocide and forcible expulsion of Greek Orthodox Christians from the country.

While Cappadocia's outdoor temperatures swing between 0 °C (32 °F) in winter and 30 °C (86 °F) in summer, the underground city temperature remains a cool 13°C (55 °F).

This makes it perfect for preserving fruit and vegetables. Today, some of the tunnels are used to store crates of pears, potatoes, lemons, oranges, apples, cabbage, and cauliflower.

Like Coober Pedy, the rock is malleable and there is little moisture in the soil, which makes tunnel construction straight-forward.

Refuge or hell?

While most people are willing to go underground for brief periods of time, the idea of living underground permanently is much harder for people to tolerate.

The underworld is synonymous with death in many cultures. Being underground in confined spaces can trigger claustrophobia, and fears of poor ventilation and cave ins.

"We do not belong there… Biologically, physiologically, our bodies are just not designed for life underground," Will Hunt, the author of Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet, told LiveScience.

Humans who live underground for too long without exposure to daylight can sleep for up to 30 hours at a time. Disruptions to their circadian rhythm can cause a range of health problems.

Another risk in underground living is flash flooding, which is of particular concern as climate change promises to bring more extreme weather events like hurricanes.

People experiencing homelessness have drowned on several occasions in the tunnels under Las Vegas. These tunnels are inhabited by around 1,500 people and are built to carry storm water. They can fill with water within minutes, leaving people no time to evacuate.

Subterranean construction usually requires heavier, pricier materials that can withstand the pressures underground. These forces must also be measured through extensive geological surveys before excavations can begin.

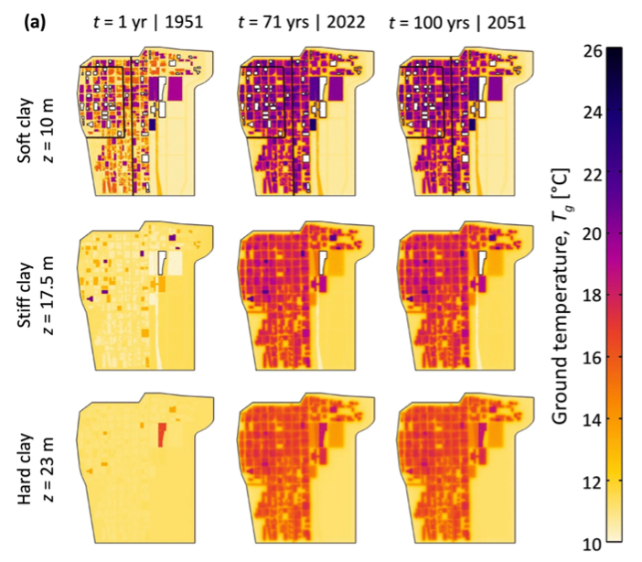

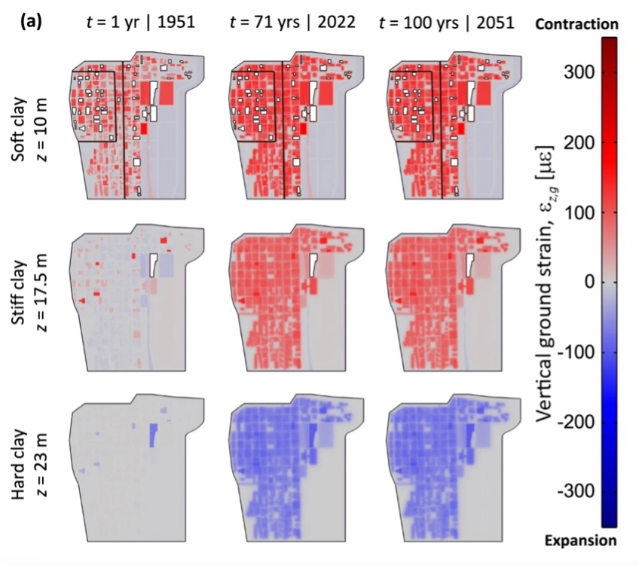

The temperature underground is also affected by what's happening above ground.

A study of the Chicago Loop business district found that temperatures have climbed dramatically since the 1950s as more heat-generating infrastructure has been built in the same area, such as parking stations, trains and basements.

The increase in temperature can cause the earth to expand up to 12 mm, which can slowly cause structural damage to buildings.

For underground environments to be acceptable to people, they must be safe and secure, have natural light, good ventilation, and provide a sense of connection with the world above.

Montreal's 20-mile-long underground city called RÉSO embodies this ideal. The complex connects buildings so that people can avoid the sub-zero temperatures outside. The space has a mix of offices, retail, hotels, and schools that blends seamlessly with the above-ground environment.

Climate change has already made some parts of Iran, Pakistan, and India dangerously hot. If the planet continues to boil, maybe we will consider building earthscrapers instead of skyscrapers?