At a newly dated 5,200 years old, the Flagstones monument in southern England is now the oldest known large stone circle in Britain.

Radiocarbon dating of some of the artifacts and remains buried beneath the monument reveals that Flagstones was erected around 3,200 BCE – at least 200 years earlier than previously thought.

This discovery is a small eureka moment, a temporal context that neatly explains the puzzling hybrid features of the monument, and suggests that Flagstones was a precursor to the stone circles that were to follow – including Stonehenge, erected 5,000 years ago.

"Flagstones is an unusual monument; a perfectly circular ditched enclosure, with burials and cremations associated with it," says archaeologist Susan Greaney of the University of Exeter in the UK.

"In some respects, it looks like monuments that come earlier, which we call causewayed enclosures, and in others, it looks a bit like things that come later that we call henges. But we didn't know where it sat between these types of monuments – and the revised chronology places it in an earlier period than we expected."

Flagstones lay hidden beneath the ground in Dorchester for thousands of years. Hints of its presence emerged in the 1890s, when a single "sarsen" – a large block of sandstone – was excavated from the garden of author Thomas Hardy, with bones and ashes buried in a pit beneath it.

The true extent of the monument, however, wasn't revealed until the 1980s, when workers digging up the ground in preparation for a road found more subterranean pits and sarsens, concealed by Earth and time, arranged in a large circle 100 meters (328 feet) in diameter.

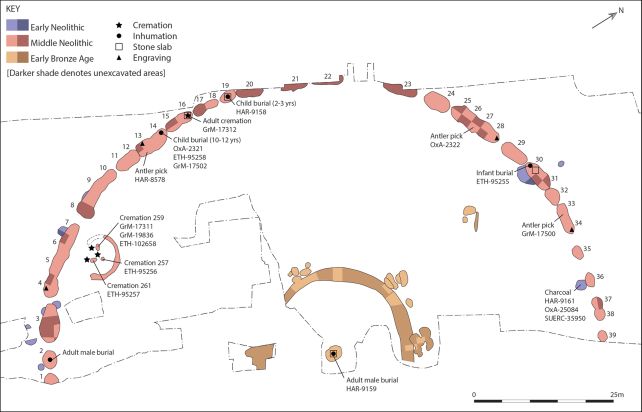

Some of the walls of the pits were engraved, and several of the pits also included human remains, some cremated, some buried children. Archaeologists have compared it to similar circular sites, all with pits and cremations, and a marked absence of other artifacts, suggesting at least a partial funerary purpose.

It seems to be part of a more widespread transition from rectangular and linear monuments to circular ones, but where it falls in the evolution of this kind of architecture has been a bit of a question, with previous dating attempts returning a broad range.

However, similarities to the cremains found beneath Stonehenge had led archaeologists to conclude that the two sites were roughly contemporaneous.

Half the monument is now buried beneath the bypass, whose construction revealed its presence in the 1980s. The other half is under Max Gate, where writer Thomas Hardy once lived.

Greaney and her colleagues conducted 23 new radiocarbon dating measurements, mostly of artifacts collected from the site during excavations in 1986 and 1987, including cremains, unburnt human bones, antler tools, and charcoal.

Their results suggest that the earliest activity, including digging the pits, took place around 3650 BCE. The circular ditched enclosure came along hundreds of years later, in 3200 BCE, with the burials placed almost immediately. One burial came along around 1000 years later, that of a young man placed beneath a large sarsen, suggesting that the site was relevant for quite a long time during the Middle Neolithic.

These results suggest that Flagstones is the oldest known large stone circle in Britain, and possibly one of the earliest constructed.

If this is the case, it could tell us something about the changing spiritual lives of the people who lived there, thousands of years ago. The shift away from burial towards cremation, and from rectangular monuments to circular ones, may reflect other broader cultural changes, for example.

"The chronology of Flagstones is essential for understanding the changing sequence of ceremonial and funeral monuments in Britain," Greaney says.

"The 'sister' monument to Flagstones is Stonehenge, whose first phase is almost identical, but it dates to around 2900 BC. Could Stonehenge have been a copy of Flagstones? Or do these findings suggest our current dating of Stonehenge might need revision?"

Whatever the answer is, the results hint at a rich, complex spiritual life and relationship with death that, thousands of years later, we can only grasp at.

The research has been published in Antiquity.