Yesterday we had news on an analysis arguing that finishing your antibiotics course might not be as necessary as we've been led to believe. Of course, it leaves us with the question how much is enough? Microbiology researcher Jonathan Cox counters it shouldn't just be 'when we feel better'.

An article in the BMJ argues that contrary to long-given advice, it is unnecessary to make sure you finish all the antibiotics you're prescribed. The article sparked debate among experts and more worryingly widespread confusion among the general public, who are still getting to grips with what they need to do to stem antibiotic resistance.

Even my colleagues at the university this morning were asking me whether or not to finish their course of antibiotics.

As an active campaigner for action to halt the progression of antibiotic resistance and a firm promoter of the "finish the course" message, the article and that the scale of coverage concerns me greatly.

While some media outlets proclaim that "we have been given the wrong advice all along", others have been more measured, suggesting that the findings of one study should not overrule 90 years of antibiotic administration.

So who is right? What the public need is clarity, not confusion. Let me make the facts clear so you can draw your own conclusion.

The original article bases its findings on a very limited set of clinical trial data for some specific infections. Their main argument is that in the trials they examined, there was no evidence that stopping treatment early increased a patient's risk of resistant infection.

Conclusive? Hardly. Let's think about the possible microbiological outcomes when you stop taking your antibiotics early.

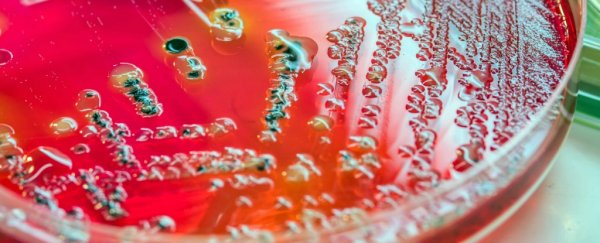

Persistent bacteria

When you have a bacterial infection that is antibiotic sensitive (so not resistant), within the first few hours to few days or in some cases months of taking a suitable dose of antibiotics, depending on the infection, there is a rapid reduction in the number of bacteria causing it.

But there remains a small population of bacteria that we refer to as "persisters" (because they persist … obviously).

Because of the reduction in the number of bacteria causing the infection at this point, the inflammation at the site of infection reduces, which means you start to feel better quickly.

But if at this point you stop taking your antibiotics because you're feeling better (as suggested in the BMJ article), in some cases those persisters can grow back and cause a recurrent (re)infection.

The bacteria that cause that recurrent infection have experienced what scientists would refer to as a sub-lethal exposure to your first antibiotic.

They may have survived simply because they were better at hiding from the antibiotic, but it is possible that they survived because they were genetically or physically better suited to dealing with that antibiotic.

If the latter is true, the persistent population in your body that is causing your recurrent infection could well be resistant to that first set of antibiotics, meaning those antibiotics may well be useless against your infection.

Antibiotic resistance is about survival of the fittest. To explain this more clearly, I have drawn a diagram (see below).

There is a big difference between persistence and resistance and one does not necessarily lead to the other. What this all comes down to is successfully treating individuals with bacterial infections.

The advice needs to be clear. No one wants to take medication unnecessarily, but sometimes feeling better doesn't mean you are better.

So, knowing what you now know, do you think stopping a course of antibiotics when you feel better as opposed to completing the course is a good idea?

It may be the case that your infection is completely clear by day two of your five-day course, but it's equally possible that a small population remains that can grow back and reinfect you.

More research and clinical trials (as also noted in the BMJ article) are required in order to fully understand and adjust the lengths of antibiotic courses, but, in my opinion as a microbiologist, the risks of taking an insufficient course significantly outweigh the benefits.

Only time will tell as to what the impact of suggesting people stop taking antibiotics when they feel better will be.

I believe this has undone a lot of the hard work scientists like myself have invested in improving antibiotic awareness and personal responsibility surrounding antibiotic administration.

Nevertheless, we all need to follow the advice of our clinicians who will no doubt hold out for some more conclusive scientific evidence before changing their advice surrounding antibiotics.

![]() As a final point for consideration, I noticed that one of the authors of the BMJ publication is a "retired building surveyor". I would take his advice on damp coursing, but perhaps seek an alternative opinion on courses of antibiotics.

As a final point for consideration, I noticed that one of the authors of the BMJ publication is a "retired building surveyor". I would take his advice on damp coursing, but perhaps seek an alternative opinion on courses of antibiotics.

Jonathan Cox, Lecturer in Microbiology, Aston University

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.