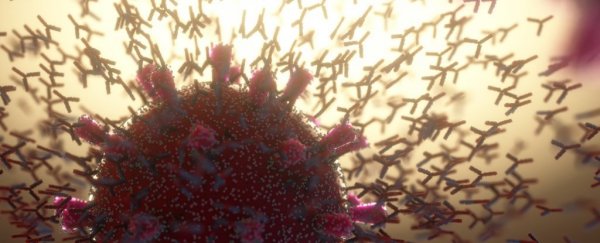

As the COVID-19 pandemic stretches towards the end of its second year, there's still much we don't know and a lot we're still learning about the antibodies we produce in response to SARS-CoV-2.

Specifically, how long do these proteins produced by the immune system last in the body, giving us some measure of built-in defense against the virus? How well do antibodies fare against different variants of the coronavirus, and how different is the protection afforded by vaccination-based antibodies from antibodies produced by prior infection?

Now, a new study led by scientists in the UK gives us a few new leads to address some of these unknowns.

First up, some good news based on the data: The blood of people who were infected in the first wave of the pandemic and then recovered, appears to retain antibodies for up to at least 10 months post onset of symptoms (POS).

"Initial concerns were that the SARS-CoV-2 antibody response might mimic that of other human endemic coronaviruses, such as 229E, for which antibody responses are short-lived and re-infections occur," the team explains in the paper, led by first author and infectious diseases researcher Liane Dupont from King's College London.

"However, our data and that of other recent studies show that although neutralizing antibody titers decline from an initial peak response, robust neutralizing activity against both pseudotyped viral particles and infectious virus can still be detected in a large proportion of convalescent sera at up to 10 months POS."

In the new study, Dupont and fellow researchers examined convalescent sera from 38 individuals, representing a mixed cohort of patients and healthcare workers, all of whom were infected in wave 1.

A previous study by some of the same team showed SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels beginning to drop after reaching peak levels at about three to five weeks POS, and it wasn't known if the drop kept happening beyond the three-month point POS.

Thankfully, the newer data show some encouraging signs. Firstly, neutralizing antibodies were still detected in convalescent sera for up to 10 months POS – the point at which the study was terminated and data processed for publication.

Secondly, there was also evidence of some cross-neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants, meaning people who were only ever exposed to the original 'wild type' SARS-CoV-2 might still have some level of protection from later, mutated variants, although at lower levels.

"Overall, wave 1 sera showed neutralizing activity against B.1.1.7 [aka the Alpha variant], P.1 [Gamma] and B.1.351 [Beta], albeit at a lower potency for B.1.1.7 and B.1.351," the researchers write.

Other results showed that infection with the SARS-CoV-2 variants – including B.1.617.2, aka Delta – "generates a cross-neutralizing antibody response that is effective against the parental virus but has reduced neutralization against divergent lineages", the researchers explain, noting that for now, vaccines developed using the spike protein from the original virus are likely to provide the broadest antibody response against current variants of concern, and newly emerging lineages.

It's worth noting that lab experiments measuring antibody activity in blood samples under glass is not the same thing as measuring people's ability to actually fight the virus off in real life, but there is still promising news here, including potentially for future vaccine research and design.

"Although sustained neutralization against the infecting SARS-CoV-2 variant is important, efficacious cross-neutralizing activity is essential for long-term protection against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants," the researchers write.

"Observations suggest that COVID-19 vaccine boosting could be an important step for increasing both neutralization breadth and vaccine efficacy against newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern."

The findings are reported in Nature Microbiology.