As the world struggles with the ongoing crisis of the coronavirus pandemic, scientists warn that the infection may pose yet another serious threat to human health, in the form of a "silent wave" of neurological consequences that could follow in the wake of the virus.

While the specific risks remain hypothetical at this point, the concerns are very real. In fact, a similar long-term effect was seen after the Spanish Flu pandemic last century.

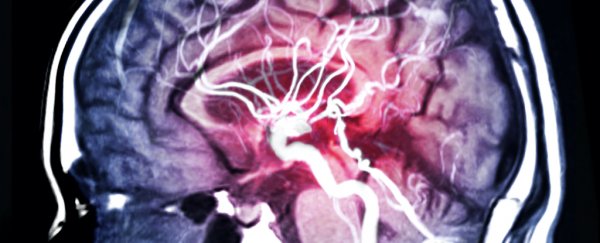

We already know that COVID-19 has links to brain damage, neurological symptoms, and memory loss. What's less clear is how the infection can bring about these crippling symptoms, in what volume, and to what ultimate effect.

"Although scientists are still learning how the SARS-CoV-2 virus is able to invade the brain and central nervous system, the fact that it's getting in there is clear," says neuroscientist Kevin Barnham from the Florey Institute of Neuroscience & Mental Health in Australia.

"Our best understanding is that the virus can cause insult to brain cells, with potential for neurodegeneration to follow on from there."

How to measure that potential is the big question.

In a new study, Barnham and his co-authors propose that the "third wave" of the COVID-19 pandemic might not be a resurgence in coronavirus infections, but a subsequent increase in viral-associated cases of Parkinson's disease, seeded by neuroinflammation, triggered in the brain as an immune response to the virus.

There's no hard evidence yet to confirm such a surge in parkinsonism will ultimately result, it's worth noting.

But something very much like this did happen once before, during the last and most comparable pandemic to grip the world: the 1918 Spanish Flu, where a form of brain inflammation called encephalitis lethargica tied to the pandemic increased the risk of parkinsonism by two to three times.

"We can take insight from the neurological consequences that followed the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918," Barnham says.

"Given that the world's population has been hit again by a viral pandemic, it is very worrying indeed to consider the potential global increase of neurological diseases that could unfold down track. The world was caught off guard the first-time, but it doesn't need to be again."

While the researchers acknowledge there is currently insufficient data to quantify the increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease in relation to COVID-19 infections, they suggest the best way of identifying future cases early would be long-term screening of SARS-CoV-2 cases post-recovery, monitoring for expressions of neurodegenerative disease.

As it happens, the new research coincides with the publication of a case report from Israel highlighting the kinds of risks Barnham and his colleagues are anticipating, even if the episode itself remains far from clear.

In what appears to be the first documented case of a patient developing Parkinson's disease after an earlier SARS-CoV-2 infection, doctors recount how a 45-year-old man was hospitalised in March with COVID-19 symptoms, experiencing cough, muscle pain, and a loss of smell.

During a following period of isolation in a COVID-19 facility, he began to experience difficulties communicating, both speaking and writing, and also showed signs of tremor and impaired walking, with subsequent testing indicating a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease.

While the man's doctors acknowledge that the mechanism bringing about his neurodegeneration is unclear, they say it's hypothetically possible his condition was triggered somehow by inflammation in the brain caused by the virus, after the infection took hold in his central nervous system.

That said, the short time window between his COVID-19 infection and the development of Parkinson's symptoms make the hypothesis unlikely, they admit, calling the temporal association "intriguing", even if we can't conclude much for certain from this isolated case.

In this case, the man had no family history of Parkinson's disease or obvious genetic signs of predisposition, but it's possible, some think, that the infection might exacerbate or accelerate the development of latent Parkinson's that hasn't yet revealed itself.

"COVID-19 infection may have been a stressor that brings previously subtle, unrecognised symptoms to a point of awareness," neurologist Alberto Espay from the University of Cincinnati, who was not involved with the case, told MedPage Today.

"It's not that those exposures caused Parkinson's but, rather they acted as precipitants, exacerbating subtle Parkinson's symptoms to a threshold of severity making them noticeable for the first time to patients and physicians."

While that's largely speculative, for now at least, it emphasises the possibility that future cases of Parkinson's after COVID-19 might be capable of detection early, if we just know what to look out for, and recognise them before the condition has fully developed, at which point mitigation is no longer an option.

"By waiting until this stage of Parkinson's disease to diagnose and treat, you've already missed the window for neuroprotective therapies to have their intended effect," Barnham says.

"Alongside a strategised public health approach, tools for early diagnosis and better treatments are going to be key."

The findings are reported in the Journal of Parkinson's Disease.