Long COVID is a brutal illness without a known mechanism or cure. Far from being psychosomatic in nature, a new study adds weight to the idea that this misunderstood disease is very much biological.

The lingering toll the SARS-CoV-2 virus exacts on the immune system is widespread and hiding in plain sight, argue researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, CellSight Technologies, and Kaiser Permanente South San Francisco Medical Center.

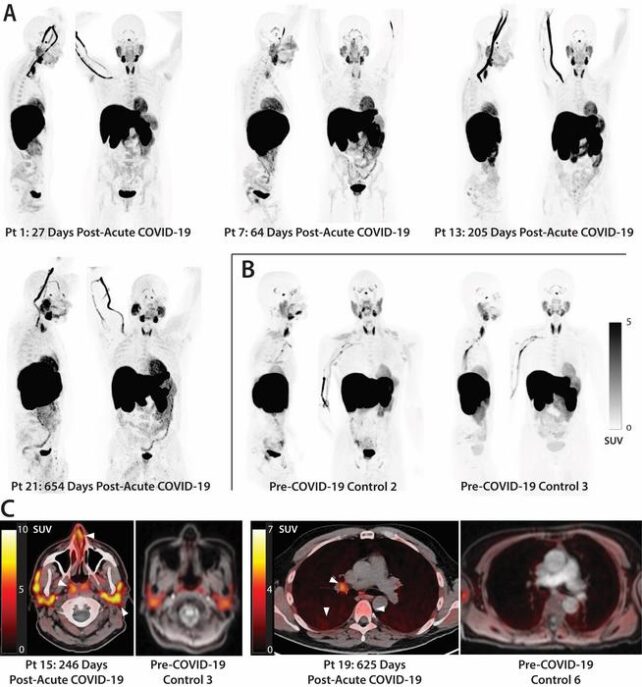

When 24 patients who had recovered from COVID-19 had their whole bodies scanned by a PET (positron emission tomography) imaging test, their insides lit up like Christmas trees.

A radioactive drug called a tracer revealed abnormal T cell activity in the brain stem, spinal cord, bone marrow, nose, throat, some lymph nodes, heart and lung tissue, and the wall of the gut, compared to whole-body scans from before the pandemic.

This widespread effect was apparent in the 18 participants with long COVID symptoms and the six participants who had fully recovered from the acute phase of COVID-19.

The activation of immune T cells in some tissues, like the spinal cord and the gut wall, was higher in patients who reported long COVID symptoms compared to those who made a complete recovery. Participants with ongoing respiratory issues also showed increased uptake of the PET tracer in their lungs and pulmonary artery walls.

That said, even those who recovered fully from COVID-19 still showed persistent changes to their T cell activity in numerous organs compared to pre- pandemic controls, in some cases two and a half years after they first contracted the virus.

"In some individuals, this activity may persist for years following initial COVID-19 onset and be associated with systemic changes in immune activation as well as the presence of [long COVID] symptoms," researchers at UCSF conclude.

"Together, these observations suggest that even clinically mild infection could have long-term consequences on tissue-based immune homeostasis and potentially result in an active viral reservoir in deeper tissues."

The findings are only correlative, but they provide compelling evidence that long COVID is tied to the persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the body and abnormal immune activity. It's worth noting that all but one participant in the study had received at least one COVID-19 vaccination prior to the PET imaging.

Long COVID is currently defined by a host of unexplained symptoms that appear after a SARS-Cov-2 infection, lasting months, or even years, with no other known cause.

Diagnosis is extremely tricky, as there can be more than 200 symptoms, which often overlap with other illnesses, such as 'brain fog', post-exertional malaise, fatigue, memory loss, or diarrhea.

Studies show that 'long haulers' can suffer from lingering issues in their heart, brain, lungs, skin, kidneys, liver, spleen, gut, thyroid, and ovaries.

One explanation for this widespread effect involves activity of the immune system. Scientists have found biomarkers of inflammation and immune activation are often present in a patient's blood after the acute phase of a viral infection.

COVID autopsies also show evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus persisting throughout the body, including in the colon, the thorax, muscles, nerves, the reproductive tract, and the eye. In some cases, remnants of the virus showed up in the brain of a deceased patient 230 days after their first initial symptoms.

Some studies even suggest an infection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus can 'reawaken' other dormant viruses in the body, like the Epstein barr virus, which has been linked to chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME).

CFS/ME shares many of the same symptoms as long COVID, and some scientists suspect they may be one and the same. Brain scans have found that long COVID changes to the brain parallel the effects of CFS/ME, and recently, a landmark study confirmed that CFS/ME is "unambiguously biological" with multiple organ systems affected.

Today, long COVID is increasingly recognized as having neurological underpinnings, and the recent discovery of T cell abnormalities in the spinal cord and brain stem suggest that these overactive immune cells are being 'trafficked' to tissues of the central nervous system.

"Overall, these observations challenge the paradigm that COVID-19 is a transient acute infection, building on recent observations in blood," the team from UCSF concludes.

The findings need to be confirmed among larger cohorts, now that this new technique for mapping the immune effects of long COVID in the body shows such great promise.

The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.