Ancient bones retrieved from an archaeological site in Germany suggest that archaic humans were peeling bears for their skins at least 320,000 years ago.

The markings found on phalanx and metatarsal paw bones of a cave bear (Ursus spelaeus or U. deningeri) represent some of the earliest known evidence of this type, and demonstrate one of the measures our ancient relatives used to survive the harsh winter conditions in the area at the time.

"The exploitation of bears, especially cave bears, has been an ongoing debate for over a century and is relevant not only in the context of hominin diets but also for the use of skins," write a team of researchers led by archaeozoologist Ivo Verheijen of the University of Tübingen in Germany.

"Tracing the origins of hide exploitation can contribute to the understanding of survival strategies in the cold and harsh conditions of Northwestern Europe during the Middle Pleistocene."

The region surrounding the German town of Schöningen has been of interest to archaeologists for decades. In the 1990s, researchers uncovered a trove of ancient artifacts from a nearby open-cut mine, including the oldest complete wooden weapons ever discovered, a set of spears dated to between 300,000 and 337,000 years ago.

Other items included stone tools, bone tools, and a number of animal bones, including those of cave bears. And many of those bones had cut marks on them – a sign that ancient humans had been butchering the animals, their tools gouging the bones as they went.

But the cut marks on the two paw bones were curious. Not only were they small and precise, the fact that they were there at all was cause for investigation.

"Cut marks on bones are often interpreted in archaeology as an indication of the utilization of meat," Verheijen explains. "But there is hardly any meat to be recovered from hand and foot bones. In this case, we can attribute such fine and precise cut marks to the careful stripping of the skin."

They compared their bones to other examples of cut marks on bear paw bones analyzed in the scientific literature, and ultimately ascribed to skinning. The cut marks on the bones found at Schöningen were similar enough for Verheijen and his team to conclude ancient humans (either Homo heidelbergensis or Neanderthals) were skinning bears when the site was in use.

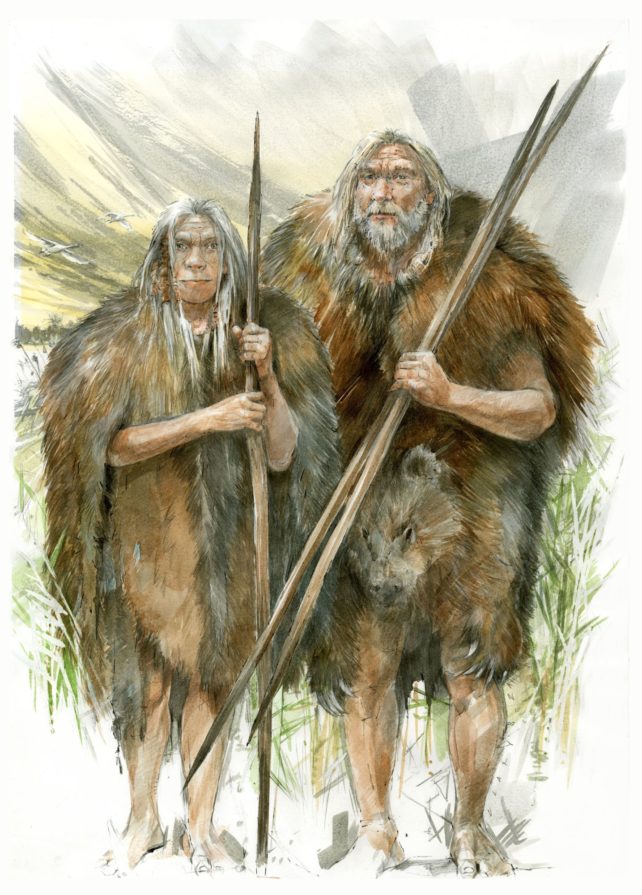

This is likely to have provided the people with better protection than their own relatively hairless hides. Bears have a thick coat at the warmest of times; in winter, it is supplemented by the growth of a soft undercoat that provides further insulation against the cold. Although the world was in an interglacial period at the time – that is, between ice ages, so relatively warm – winters would still have been harsh.

"These newly discovered cut marks are an indication that about 300,000 years ago, people in northern Europe were able to survive in winter thanks in part to warm bear skins," Verheijen says.

This naturally raises the question of how the skins were obtained. In order to be usable, a bear's skin needs to be stripped pretty quickly after death, so sitting around just waiting for a cave bear to drop dead is unlikely to be a useful strategy. Luckily, the bones and weapons found at the site suggest an answer.

"If only adult animals are found at an archaeological site, this is usually considered an indication of hunting," Verheijen says. "At Schöningen, all the bear bones and teeth belonged to adult individuals."

So, taken together, the bear remains at Schöningen suggest that humans were hunting bears, then skinning them for their luxurious pelts. How exactly they used these pelts remains open to speculation, but it's unlikely such groups of human would have been walking around naked, the researchers say; therefore, the likelihood is that they skins were used for either wearing, or sleeping.

The research has been published in the Journal of Human Evolution.