A new mouse study challenges conventional wisdom that cutting down on calories can lead to a drop in exercise performance. Even when dieting, it seems mammalian bodies are able and willing to keep up previous activity levels.

Researchers looked at mice that spent time on a treadmill as their diets were cut down. These lab tests are easier to get fixed figures from, compared to real-world conditions, where our relationships to dieting and exercise are often irregular and hard to quantify.

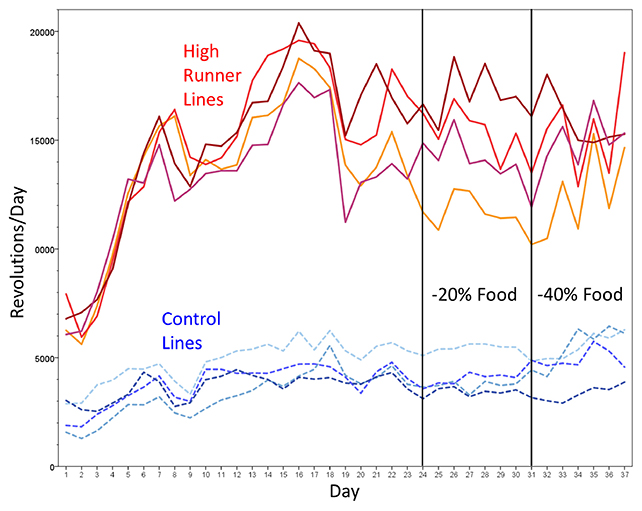

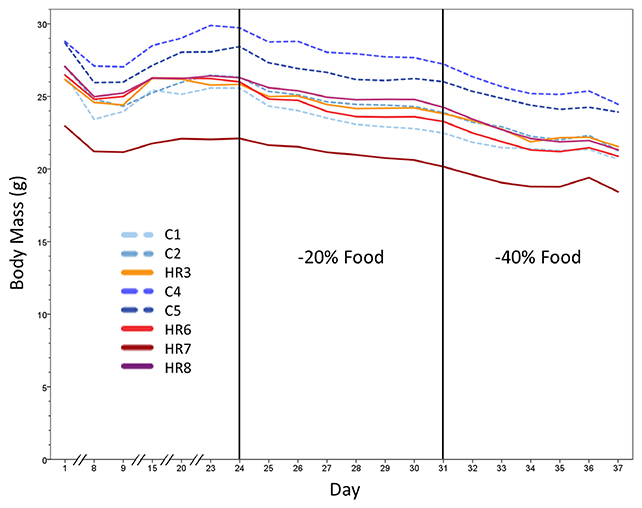

After three weeks of baseline measurements, the team led by researchers from the University of California, Riverside (UCR) cut down the calories given to the mice by 20 percent for one week, and then by 40 percent the following week. They included normal mice as well as 'high-runner' mice bred to enjoy running.

"Voluntary exercise [in mice] was remarkably resistant to reducing the amount of food by 20 percent and even by 40 percent," says biologist Theodore Garland Jr from UCR. "They just kept running."

The only significant reduction in running noted by the researchers was a drop in distance of 11 percent in the high-runner mice on the strictest diets. As these mice run three times more than normal anyway, that's not considered to be a major variation.

In all the other scenarios, the running regimes stayed the same. What's more, the body mass of the mice stayed the same with a 20 percent drop in calories, with a small reduction in body mass noted at the 40 percent drop level.

That's a surprising finding, which hasn't been seen in other similar studies, and the researchers think that there might be some kind of balancing mechanism going on that means weight isn't lost as it normally would be.

"There has to be some type of compensation going on if your food goes down by 40 percent and your weight doesn't go down very much," says Garland.

"Maybe that's reducing other types of activities, or becoming metabolically more efficient, which we didn't yet measure."

Even when dieting, it's important to keep up with exercise for our overall health, and this study shows – in mice at least – that the body should be able to cope with having less food while still maintaining the same level of activity.

Indeed, there's plenty of evidence that diets have to be combined with exercise in order for them to be effective. In a world that's grappling with increasing levels of obesity and its health implications, it's important to understand the science of weight loss.

"We don't want people on diets to say, I don't have enough energy, so I'll make up for it by not exercising," says Garland.

"That would be counterproductive, and now we know, it doesn't have to be this way."

The research has been published in Physiology & Behavior.