A new study suggests a key compound in foods like broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage can reduce blood sugar levels, potentially providing an inexpensive, affordable way to prevent type 2 diabetes from developing.

The study involved 74 people aged between 35 and 75 with rising blood sugar levels that categorize them as prediabetic. All the participants were also overweight or obese.

Volunteers were given either a compound commonly found in cruciferous vegetables known as sulforaphane or a placebo every day for 12 weeks. Those given sulforaphane showed a significant reduction in blood sugar, report the researchers, led by a team from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

"The treatment of prediabetes is currently lacking in many respects, but these new findings open the way for possible precision treatment using sulforaphane extracted from broccoli as a functional food," says Anders Rosengren, a molecular physiologist at the University of Gothenburg.

For some individuals within the test group, the reduction in blood sugar levels was even more considerable: those with early signs of mild age-related diabetes, a relatively low BMI, low insulin resistance, a low incidence of fatty liver disease, and low insulin secretion saw a drop that was double the average.

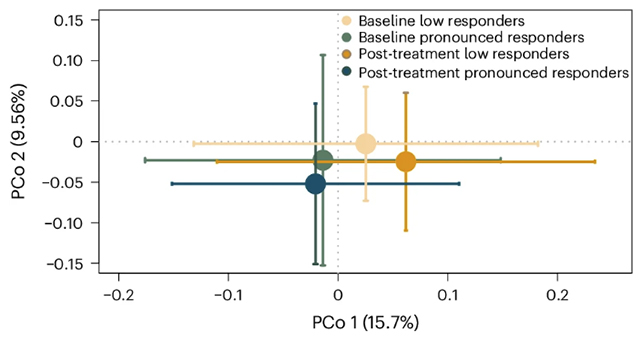

Gut bacteria also seems to make a difference. The team identified the bacterial gene BT2160 – known to be involved in sulforaphane activation – as significant, those with more of this gene in their gut bacteria showed an average blood sugar drop of 0.7 millimoles per liter, compared to 0.2 mmol/L for sulforaphane vs placebo overall.

These variations demonstrate the need for personalized approaches to prediabetes. The more we know about which groups of people get the best response from which treatments, the more effective those treatments will be.

"The results of the study also offer a general model of how pathophysiology and gut flora interact with and influence treatment responses – a model that could have broader implications," says Rosengren.

Prediabetes is estimated to affect hundreds of millions of people globally, and incidence rates are rising fast. As many as 70 to 80 percent of people with prediabetes will then go on to develop diabetes, though the figure varies considerably depending on gender and the definitions used.

There's clearly an urgent need to prevent the transition from one condition to the next – and all the health implications – but prediabetes often goes undiagnosed or untreated. These new findings could certainly help, but the researchers also emphasize the importance of a holistic approach in reducing diabetes risk.

"Lifestyle factors remain the foundation of any treatment for prediabetes, including exercise, healthy eating, and weight loss," says Rosengren.

The research has been published in Nature Microbiology.