This year is increasingly likely to be the planet's second- or third-warmest calendar year on record since modern temperature data collection began in 1880, according to data released this week by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

This reflects the growing influence of long-term, human-caused global warming and is especially noteworthy, as there was an absence of a strong El Niño in the tropical Pacific Ocean this year.

Such events are typically associated with the hottest years, since they boost global ocean temperatures and add large amounts of heat to the atmosphere across the Pacific Ocean, the world's largest.

According to a new report released Monday, there's about an 85 percent chance that the year will wind up ranking as the second-warmest in NOAA's data set, with a possibility that it slips to No. 3.

Overall, though, it's virtually certain (greater than a 99 percent chance) that 2019 will wind up being a top-five-warmest year for the globe.

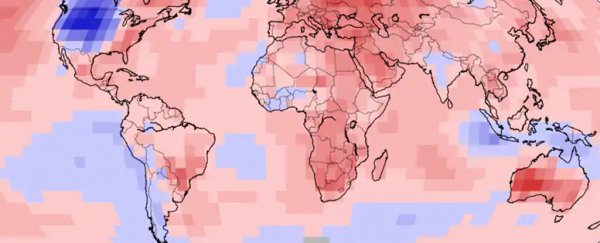

Global land and ocean temperature departures from average for October 2019. (NOAA)

Global land and ocean temperature departures from average for October 2019. (NOAA)

NOAA found the average global land and ocean surface temperature for October was 1.76 degrees (0.98 degrees Celsius) above the 20th-century average, 0.11 of a degree shy of the record warm October set in 2015.

Remarkably, the 10 warmest Octobers have occurred since 2003, and the top-five warmest such months have taken place since 2015.

October 2019 was the 43rd-straight October to be warmer than the 20th-century average, and the 418th straight warmer-than-average month. This means anyone younger than 38 has not lived through a cooler-than-average year from a global standpoint.

So far this year, global land and ocean temperatures have come in at 1.69 degrees (0.94 Celsius) above the 20th-century average, 0.16 of a degree cooler than the record warmest year-to-date, set in 2016, NOAA found.

Other agencies that track global temperatures may rank 2019 slightly differently than NOAA will, although their overall data is likely to be similar.

NASA, for example, interpolates temperatures across the data-sparse Arctic by assuming the temperatures region-wide are similar to their closest observation location. NOAA, on the other hand, leaves parts of the Arctic out of its data.

Considering the Arctic is warming at more than twice the rate of the rest of the world, this means NOAA's data could be slightly underestimating global temperatures, though it wouldn't be by much.

In an illustration of the differences that can occur between monitoring agencies, the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service ranked October as Earth's hottest such month, slightly edging out October 2016. NASA and NOAA, on the other hand, ranked October second on their lists.

Copernicus uses computer modeling data to monitor the planet's climate in near-real-time, compared to the surface weather stations that NASA and NOAA rely on, which can be prone to biases involving their precise siting, and other issues. However, both agencies work to adjust their records to remove such issues.

At the end of the day, what matters is the long-term trend over many years to decades, and that shows a clear, sharp spike that scientists have shown can be explained only by increasing amounts of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, in the atmosphere.

Human activities, namely burning fossil fuels such as coal and oil for energy, are the main contributors of greenhouse gases.

According to NOAA, record warm October temperatures were existed across parts of the North and Western Pacific Ocean, northeastern Canada, as well as scattered across parts of the South Atlantic Ocean, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, the Indian Ocean and South America.

Trend in global ocean heat content since 1955. (NOAA)

Trend in global ocean heat content since 1955. (NOAA)

The only region of record cold for the month was in the Western United States, where much of the Rockies were at record cold for the month.

Interestingly, despite the absence of a declared El Niño in the tropical Pacific, global average sea-surface temperatures ranked second-warmest on record for the month, running less than a tenth of a degree behind the record year of 2016, when there was an intense El Niño event.

The oceans are absorbing the vast majority of the extra heat being pumped into the climate system because of the buildup of greenhouse gases, with heat content as measured underneath the surface hitting record levels.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.