The world is in the midst of an antibiotic resistance crisis that contributes to the death of nearly 5 million people a year. But bacteria aren't the only mutating pathogens we need to worry about.

Fungal infections are also adapting beyond the means of our medicine, causing a "silent pandemic" that needs to be addressed urgently, according to some researchers.

"The threat of fungal pathogens and antifungal resistance, even though it is a growing global issue, is being left out of the debate," explains molecular biologist Norman van Rhijn from the University of Manchester in the UK.

This September, the United Nations is hosting a meeting in New York City on antimicrobial resistance, which includes discussions on resistant bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites.

Ahead of this event, van Rhijn and an international team of scientists are urging governments, the research community, and the pharmaceutical industry to "look beyond just bacteria."

Fungal infections, they write in a correspondence for The Lancet, are left out of too many initiatives to tackle antimicrobial resistance.

Without urgent attention and action, some particularly nasty fungal infections, which already infect 6.5 million a year and claim 3.8 million lives annually, could become even more dangerous.

"The disproportionate focus on bacteria is concerning because many drug resistance problems over the past decades were the result of invasive fungal diseases, which are largely under-recognized by the community and governments alike," write van Rhijn and his colleagues, who hail from institutions in China, the Netherlands, Austria, Australia, Spain, the UK, Brazil, the US, India, Türkiye, and Uganda.

In 2022, the World Health Organization published the Fungal Priority Pathogen List – "the first global effort to systematically prioritize fungal pathogens".

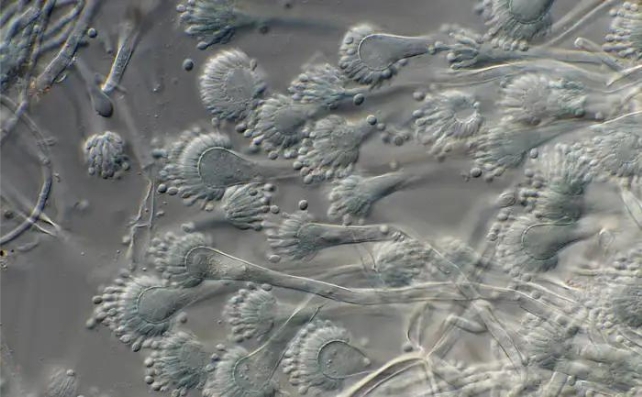

The pathogens considered most dangerous to human health included Aspergillus fumigatus, which comes from mold and infects the respiratory system; Candida, which can cause a yeast infection; Nakaseomyces glabratus, which can infect the urogenital tract or bloodstream; and Trichophyton indotineae, which can infect the skin, hair, and nails.

Older folk or those who are immunocompromised are the most at risk.

Compared to bacteria or viruses, fungi are more complicated organisms, most similar to animals in their structure. This makes it harder and more expensive for scientists to develop medicine that kills the cells of fungi without damaging other important cells in the body.

"To treat deep or invasive fungal infections, only four systemic antifungal classes are available and resistance is now the rule rather than the exception for those currently available classes," write the authors of the correspondence.

In the past few decades, several promising new antifungals have come to light, but the arms race between pathogen and medicine is being sped up in part by the agrochemical industry.

"Even before [these drugs] reach the market after years of development and clinical trials, fungicides with similar modes of action are developed by the agrochemical industry resulting in cross-resistance for critical priority pathogens," explain the researchers in their correspondence.

"Antifungal protection is required for food security. The question is, how do we balance food security with the ability to treat current and future resistant fungal pathogens?"

It's a conundrum that has been discussed at length for antibiotics but not so much for antifungals. Van Rhijn and his team recommend a global agreement to limit certain antifungal drugs to specific purposes, as well as collaborative regulations to balance food security with health.

The UN's meeting this September "must serve as a starting point" for an orchestrated and diverse approach to antimicrobial resistance, the researchers conclude.

No microbe should be left behind.

The study was published in The Lancet.