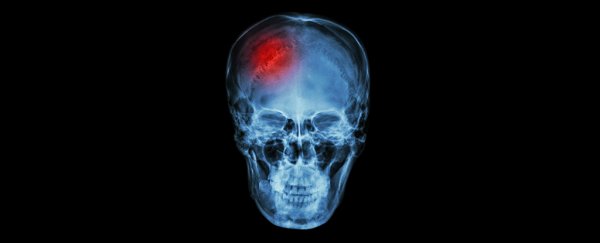

As if experiencing a traumatic brain injury wasn't enough of a problem on its own, it turns out the consequences can have an unusual effect on a remote part of the body – the lower intestine.

Researchers have long been puzzled by the connection between these apparently distinct body systems, but now suspect the relationship can cause the colon to leak bacteria into the blood, turning minor brain damage into a deadly infection.

A team of researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) in the US has led a study finding traumatic brain injuries (TBI) could increase the permeability of the colon, potentially opening the way for intestinal bacteria to slip into circulation.

"These results indicate strong two-way interactions between the brain and the gut that may help explain the increased incidence of systemic infections after brain trauma and allow new treatment approaches," says Alan Faden, the study's lead researcher and director of the UMSOM Shock, Trauma and Anaesthesiology Research Centre.

Sepsis is also considered to be a massive problem in patients with a TBI. Even those who survive their first year are reported to still be two and a half times more likely to die from problems with their digestive system.

So something seems to be going on between damaged brain tissue and the gut. To look for clues, the team examined tissue samples taken from the digestive systems of mice with controlled cortical damage a day after the injury, and then 28 days later.

They found the brain damage was associated with distinct changes to the colon, differences that were evident after a month. These changes included a thickening of the mucosal tissue and the smooth muscle, as well as an increase in its permeability to fluids.

Infecting the injured mice with a rodent gut microbe called Citrobacter rodentium worsened the inflammation surrounding their injury and caused significant changes to other parts of their brain.

The results indicate that a leaky gut caused by TBI can potentially raise the risk of letting in microbes that only make the injury worse – a deadly two-way street that we're only beginning to understand.

Exactly how damage to the brain's tissues makes the colon thicker and more permeable isn't all that clear.

One hypothesis centres on glials – nanny cells that help support neurons in both the brain and around the gut.

Perhaps signals responding to trauma in the brain could be alerting both astroglials in the brain and enteric glial cells surrounding the colon.

"These results really underscore the importance of bi-directional gut-brain communication on the long-term effects of TBI," says Faden.

More work needs to be done, no doubt. Given the current model is based on mice, we also need to keep an open mind on potential physiological differences between them and humans.

But it's an interesting observation, one that only adds further to our growing understanding of how tightly linked these two systems are.

Recent studies have also shown a relationship between strokes and bacteria in the digestive system, as well as gut microbes and neurological diseases such as Parkinson's.

It's quite a distance between the sewer end of the intestines and the body's penthouse suite in the brain. But the more we learn about how closely they work together, the better we'll be able to avert disastrous consequences when that link goes wrong.

This research was published in Brain, Behaviour, and Immunity.