A close study of 40 years' worth of data has revealed something a little hinky going on with Jupiter.

According to a wealth of information collected by both ground- and space-based telescopes, the temperature in Jupiter's upper troposphere exhibits regular fluctuations that don't seem to be tied to any seasonal variations. This surprising and intriguing finding could help scientists finally understand the gas giant's strange weather.

"We've solved one part of the puzzle now, which is that the atmosphere shows these natural cycles," says planetary scientist Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester in the UK.

"To understand what's driving these patterns and why they occur on these particular timescales, we need to explore both above and below the cloudy layers."

It ought to surprise no one that Jupiter, the largest planet in the Solar System, is very unlike our lovely habitable home world. It's whipped by wild winds, clad in thick layers of clouds, and speckled with tempestuous storms that can grow to sizes larger than Earth. Its extreme weather is so very alien that scientists have struggled to understand it.

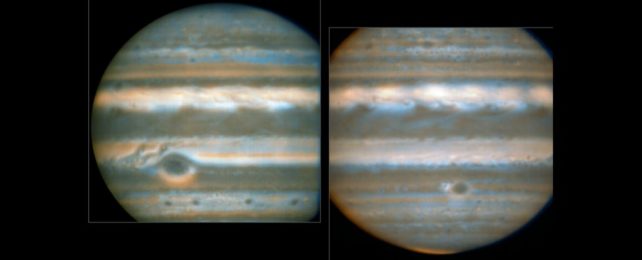

We know that it's ringed by alternating bands of light and dark clouds known as zones and belts that rotate around the planet in opposite directions. We also know, from infrared images, that the darker belts are warmer at least partially because the clouds are thinner, allowing more heat to escape from the planetary interior.

The other interesting thing about Jupiter is that it doesn't have much of a tilt. The axis around which the planet rotates lists by a mere 3 degrees in relation to its orbital plane around the Sun. Here on Earth, and other planets like Mars and Saturn, a strong axial tilt (23.4 degrees for Earth) points the poles towards or away from the Sun, causing distinct seasonal variations in temperature.

Scientists never expected Jupiter to experience significant cycles in temperature variation, but until now, long-term datasets on the planet's heat profile haven't been available to check whether this was the case. Until now.

Data from instruments aboard the Voyager and Cassini space probes, and from the Very Large Telescope, the Subaru Telescope and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility, gave a team led by planetary scientist Glenn Orton of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory decades worth of thermal data to work with.

To their surprise, they found temperature fluctuations with periodicities of 4, 7 to 9, and 10 to 14 years, involving different latitude bands. These seem disconnected, they found, from seasonal temperature variations.

However, there is some internal consistency: as temperatures rise at specific latitudes in the northern hemisphere, they go down at corresponding latitudes in the southern hemisphere, specifically at 16, 22, and 30 degrees. It's as though Jupiter is a mirror of itself, split by the equator, maintaining thermal balance.

"That was the most surprising of all," Orton says.

"We found a connection between how the temperatures varied at very distant latitudes. It's similar to a phenomenon we see on Earth, where weather and climate patterns in one region can have a noticeable influence on weather elsewhere, with the patterns of variability seemingly 'teleconnected' across vast distances through the atmosphere."

It's unclear what drives or links these temperature fluctuations, but a clue can be found higher in Jupiter's atmosphere, in the clear stratospheric layer that sits above the cloudy troposphere. At Jupiter's equator, temperature variations in the troposphere are matched by an opposite variation in the stratosphere. This suggests that whatever is happening at higher altitudes is influencing what is happening below, or vice versa.

And whatever that might be, this study is a very important piece of the puzzle that may, one day, help scientists be able to accurately understand and predict Jovian weather.

"Measuring these temperature changes and periods over time is a step toward ultimately having a full-on Jupiter weather forecast, if we can connect cause and effect in Jupiter's atmosphere," Fletcher says. "And the even bigger-picture question is if we can someday extend this to other giant planets to see if similar patterns show up."

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.