It's a common refrain from those who question mainstream climate science findings: The computer models scientists use to project future global warming are inaccurate and shouldn't be trusted to help policymakers decide whether to take potentially expensive steps to rein in greenhouse gas emissions.

A new study effectively snuffs out that argument by looking at how climate models published between 1970 - before such models were the supercomputer-dependent behemoths of physical equations covering glaciers, ocean pH and vegetation, as they are today - and 2007.

The study, published Wednesday in Geophysical Research Letters, finds that most of the models examined were uncannily accurate in projecting how much the world would warm in response to increasing amounts of planet-warming greenhouse gases. Such gases, chiefly the main long-lived greenhouse gas pollutant, carbon dioxide, hit record highs this year, according to a new UN report out Tuesday.

They are now higher than at any other time in human history.

The study does fault some of the models, including one of the most famous calculations by former NASA researcher James Hansen, for overestimating warming because they assumed there would be even greater amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere than what actually occurred. These assumptions mostly involved non-CO2 greenhouse gases, such as methane.

Hansen's projection, says study lead author Zeke Hausfather, a researcher at the University of California at Berkeley, erred by about 50 percent because it did not foresee a significant drop in emissions of substances that deplete the stratospheric ozone layer.

Many of those gases are also powerful global warming agents. Hansen also didn't foresee a temporary stabilization in methane emissions during the 2000s, Hausfather says.

However, his model, like many of the others examined in the new study, got it right on the basic relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and the amount of warming they would cause. The errors came from poorly predicting bigger wild cards: How societal factors would govern future emissions through economic growth, emissions reduction agreements, and other factors.

"The big takeaway is that climate models have been around a long time, and in terms of getting the basic temperature of the Earth right, they've been doing that for a long time," Hausfather said in an interview.

By examining past model performance, Hausfather says researchers can get a better idea of the pros and cons of the newest generations of models. This is crucial, since scientists are just now rolling out the next suite of models to inform the upcoming UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's 6th Assessment Report, due out in 2022.

"Climate models today aren't perfect, they're still being improved," he says.

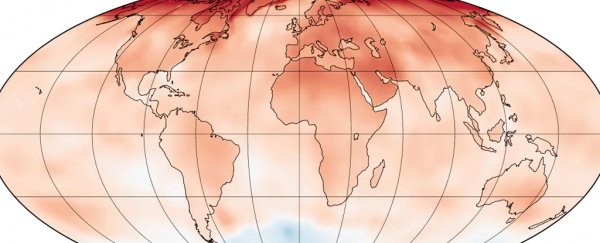

(Hausfather et. al. 2019/Zeke Hausfather)

(Hausfather et. al. 2019/Zeke Hausfather)

Image: Comparison of trends in temperature vs. time (top) and implied transient climate response, or the amount of temperature increase that might take place when carbon dioxide doubles (bottom) between observations and models over the periods displayed.

While a figure (above) and calculations included in the study seems to show that many of the models had a slight warm bias over time, Hausfather says the study found "no detectable consistent overestimation or underestimation of future warming" in the models that were examined.

On temperature, there's considerable confidence that the current models are accurately capturing the planet's response to record amounts of greenhouse gases in the air.

However, there are many other aspects of a changing climate that contain bigger uncertainties, such as cloud formation and how small atmospheric particles known as aerosols could alter the types of clouds that form.

This could either enhance or diminish warming.

In addition, precipitation changes, particularly at a regional level, are still extremely difficult for modelers to capture, Hausfather says.

"Temperature is easy, other climate variables like precipitation are a lot harder."

For the study, researchers evaluated climate models on how they performed regarding the amount of projected global mean temperature change compared to what actually took place over time.

On this count, 10 out of the 17 models examined were virtually indistinguishable from observations, the study found - in other words a near-perfect match.

They also looked at the relationship between a model's temperature projection and the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, also known as external forcing. On this comparison, 14 out of the 17 models "were not differentiable from observations," and two of the 14 showed more warming than actually occurred, with one showing less warming, Hausfather says.

"We argue that second test is a more accurate one," Hausfather says, because it allows scientists to control for the fact that models might get the amount of external forcing wrong, but the relationship between greenhouse gases and temperature change correct.

"By looking at this relationship between temperature and forcing, we can evaluate the model's performance on its physics and not on its crystal ball of future emissions," Hausfather said.

Researchers who were not involved in the new study said it employed relatively simple statistical analyses that may miss some key influences on global surface temperatures over time.

For example, Kevin Trenberth, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said he has doubts about the study's key conclusion that "climate models are effectively capturing the processes" that drive the global mean surface temperature over many decades.

He says the reality is more complex than the study shows, since some of the more uncertain factors about climate change, such as how the water cycle is responding as the world warms, could influence global temperatures, as do hurricanes and aerosols, which are either not included in climate models or, in the case of aerosols, a big question mark since they can influence cloud formation that in turn can alter temperatures.

According to Trenberth, the mere fact that the models have been generally on target doesn't prove that they are getting such complex processes correct, and further research is necessary for that.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.