Imagine you're a fossil hunter. You spend months in the heat of Arizona digging up bones only to find that what you've uncovered is from a previously discovered dinosaur.

That's how the search for antibiotics has panned out recently. The relatively few antibiotic hunters out there keep finding the same types of antibiotics.

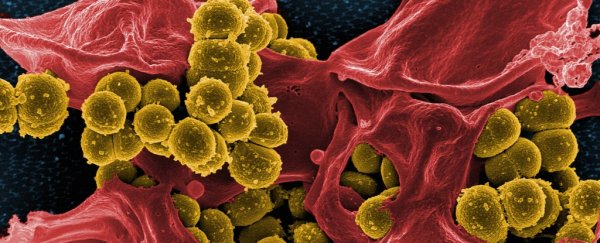

With the rapid rise in drug resistance in many pathogens, new antibiotics are desperately needed. It may be only a matter of time before a wound or scratch becomes life-threatening.

Yet few new antibiotics have entered the market of late, and even these are just minor variants of old antibiotics.

While the prospects look bleak, the recent revolution in artificial intelligence (AI) offers new hope. In a study published on Feb. 20 in the journal Cell, scientists from MIT and Harvard used a type of AI called deep learning to discover new antibiotics.

The traditional way of discovering antibiotics – from soil or plant extracts – has not revealed new candidates, and there are many social and economic hurdles to solving this problem, as well.

Some scientists have recently tried to tackle it by searching the DNA of bacteria for new antibiotic-producing genes. Others are looking for antibiotics in exotic locations such as in our noses.

Drugs found through such unconventional methods face a rocky road to reach the market. The drugs that are effective in a petri dish may not work well inside the body.

They may not be absorbed well or may have side effects. Manufacturing these drugs in large quantities is also a significant challenge.

Deep learning

Enter deep learning. These algorithms power many of today's facial recognition systems and self-driving cars. They mimic how neurons in our brains operate by learning patterns in data.

An individual artificial neuron – like a mini sensor – might detect simple patterns like lines or circles. By using thousands of these artificial neurons, deep learning AI can perform extremely complex tasks like recognizing cats in videos or detecting tumors in biopsy images.

Given its power and success, it might not be surprising to learn that researchers hunting for new drugs are embracing deep learning AI. Yet building an AI method for discovering new drugs is no trivial task. In large part, this is because in the field of AI there's no free lunch.

The No Free Lunch theorem states that there is no universally superior algorithm. This means that if an algorithm performs spectacularly in one task, say facial recognition, then it will fail spectacularly in a different task, like drug discovery. Hence researchers can't simply use off-the-shelf deep learning AI.

The Harvard-MIT team used a new type of deep learning AI called graph neural networks for drug discovery. Back in the AI stone age of 2010, AI models for drug discovery were built using text descriptions of chemicals. This is like describing a person's face through words such as "dark eyes" and "long nose."

These text descriptors are useful but obviously don't paint the entire picture. The AI method used by the Harvard-MIT team describes chemicals as a network of atoms, which gives the algorithm a more complete picture of the chemical than text descriptions can provide.

Human knowledge and AI blank slates

Yet deep learning alone is not sufficient to discover new antibiotics. It needs to be coupled with deep biological knowledge of infections.

The Harvard-MIT team meticulously trained the AI algorithm with examples of drugs that are effective and those that aren't. In addition, they used drugs that are known to be safe in humans to train the AI.

They then used the AI algorithm to identify potentially safe yet potent antibiotics from millions of chemicals.

Unlike people, AI has no preconceived notions, especially about what an antibiotic should look like. Using old-school AI, my lab recently discovered some surprising candidates for treating tuberculosis, including an anti-psychotic drug.

In the study by the Harvard-MIT team, they found a gold mine of new candidates. These candidate drugs do not look anything like existing antibiotics. One promising candidate is Halicin, a drug being explored for treating diabetes.

Halicin, surprisingly, was potent not only against E. coli, the bacteria the AI algorithm was trained on, but also on more deadly pathogens, including those that cause tuberculosis and colon inflammation.

Notably, Halicin was potent against drug resistant Acinetobacter baumanni. This bacterium tops the list of most deadly pathogens compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Unfortunately, Halicin's broad potency suggests that it may also destroy harmless bacteria in our body. It may also have metabolic side effects, since it was originally designed as an anti-diabetic drug. Given the dire need for new antibiotics, these may be small sacrifices to pay to save lives.

Keeping ahead of evolution

Given the promise of Halicin, should we stop the search for new antibiotics?

Halicin might clear all hurdles and eventually reach the market. But it still needs to overcome an unrelenting foe that's the main cause of the drug resistance crisis: evolution.

Humans have thrown numerous drugs at pathogens over the past century. Yet pathogens have always evolved resistance. So it likely wouldn't be long until we encounter a Halicin-resistant infection.

Nevertheless, with the power of deep learning AI, we may now be better suited to quickly respond with a new antibiotic.

Many challenges lie ahead for potential antibiotics discovered using AI to reach the clinic. The conditions in which these drugs are tested are different from those inside the human body.

New AI tools are being built by my lab and others to simulate the body's internal environment to assess antibiotic potency. AI models can also now predict drug toxicity and side effects.

These AI technologies together may soon give us a leg up in the never-ending battle against drug resistance.

[You're smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation's authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.] ![]()

Sriram Chandrasekaran, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan.

This article is republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.