What is it about spiders and their eight arched legs – sometimes fat and furry, or thin like dark needles – crawling close, ever closer to our skin, that provokes such fear and outright revulsion?

It's long been debated whether arachnophobia is something that's embedded into us as a species – or whether we learn it from culture – so to tease out the answer, scientists recruited the most innocent and neutral of study participants: human babies.

With these unsuspecting infants on hand, researchers led by the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Germany exposed the six-month-olds to images of eight-legged nightmare fuel to measure their innate, untrained responses to the arachnids.

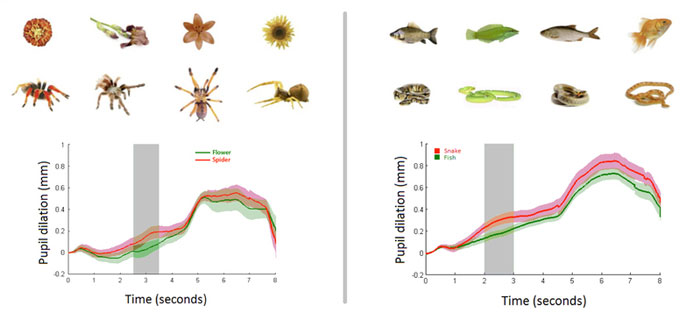

In addition to images of spiders, the infants, sitting safely on a parent's lap, were also shown pictures of flowers, while in a separate experiment, the babies looked at a series of images showing either snakes or fish.

MPI CBS

MPI CBS

During the experiment, the babies had their pupillary dilation measured by an infrared eye tracker, which indicates levels of the fight-or-flight chemical norepinephrine (aka noradrenaline), and so can help gauge stress response.

"When we showed pictures of a snake or a spider to the babies instead of a flower or a fish of the same size and colour, they reacted with significantly bigger pupils", says neuroscientist Stefanie Hoehl from the Max Planck Institute and the University of Vienna in Austria.

"In constant light conditions this change in size of the pupils is an important signal for the activation of the noradrenergic system in the brain, which is responsible for stress reactions. Accordingly, even the youngest babies seem to be stressed by these groups of animals."

In the case of spiders, average pupil dilations were 0.14 mm, whereas flowers only received 0.03 mm.

The differences weren't as significant in the case of snakes and fish, which the researchers suggest could be because both images depicted live animals, eliciting more similar responses.

But in any case, spiders and snakes provoked the most pupil dilation, even in children that are so young they couldn't possibly have learned that spiders are something dangerous that many older people tend to fear. But why?

"We conclude that fear of snakes and spiders is of evolutionary origin," Hoehl explains.

"Similar to primates, mechanisms in our brains enable us to identify objects as 'spider' or 'snake' and to react to them very fast."

As for how such a hypothetical mechanism could exist, the researchers don't know for sure, but the idea is that somehow, over countless generations in ancient times, our human ancestors evolved a trait "that ensures special attention and facilitated fear-learning for ancestral threats in early human ontogeny", the team explains in their paper.

In other words, even though our sheltered, modern lives mean most of us rarely come into contact with dangerous snakes or spiders, our long-forgotten forebears weren't so lucky – and the fear and disgust some of us feel today when we encounter these critters could actually be a hangover from a survival instinct that evolved in ancient times.

So next time you're shuddering as you watch that eight-legged demon scramble behind the fridge, embrace the fear – after all, it could be good for you.

The findings are reported in Frontiers in Psychology.