"Zombie cells" that contribute to age-related diseases also help heal damaged tissues, so wiping them out could come with major downsides, a new study suggests.

The zombies, scientifically known as "senescent" cells, are cells that stop multiplying due to damage or stress but don't die, according to the National Institute on Aging.

Instead, these cells release a slew of molecules that summon immune cells and spark inflammation. The immune system clears these zombies from the body, but with age, it becomes less efficient; thus, the cells accumulate and drive inflammation that contributes to diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and osteoarthritis.

But zombie cells aren't entirely bad.

The new study, conducted in lab mice and human cells, suggests that senescent cells help repair lung tissue after damage by encouraging stem cells to grow.

Killing these cells with dasatinib and quercetin (DQ) – a drug duo that's been studied as a potential treatment to combat aging and age-related disease – disrupted this repair, the researchers reported 13 October in the journal Science.

Related: Anti-aging vaccine shows promise in mice

"We are not the first lab to implicate senescence as a wound-healing process," said senior author Tien Peng, an associate professor of pulmonary, critical care, allergy and sleep medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

A 2014 study in the journal Developmental Cell found that zombie cells help mend wounds in the skin and that their repairs can also be disrupted by zombie-slaying drugs, or "senolytics."

This suggests that using senolytics could come at a cost, so the drugs will have to be designed to block zombie cells' bad effects without disrupting their good ones, Peng told Live Science.

How 'zombies' heal damaged tissues

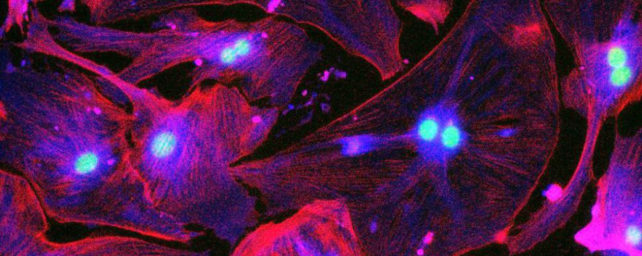

To find senescent cells in the lung, researchers genetically modified mice to carry a glowing protein on the gene that codes for the protein "p16," which is overactive in many senescent cells.

Whenever a cell switched on the gene, it would also churn out fluorescent proteins and start to glow.

The researchers used a technique to "really amplify this signal," Peng said, and thus revealed cells that carry low levels of p16 and may have otherwise escaped notice.

Glowing cells appeared in mice's lungs shortly after birth, and their numbers increased over the rodents' life spans.

The cells included fibroblasts, which make connective tissue, as well as immune cells, and resided within a sheet-like tissue called the "basement membrane" that supports the lining of the lungs' air sacs, air tubes, and blood vessels.

This sheet blocks harmful chemicals and pathogens from entering the lungs while also allowing oxygen to pass into the bloodstream.

The p16-carrying cells act as guardians of this crucial interface.

After an injury, immune cells rush in to repair the damage and release a flurry of signals that call p16-carrying cells into action.

The immune cells increase in number, and the fibroblasts gush compounds that summon more immune cells and spur stem cell growth.

Giving the mice DQ cuts off this signaling cascade and thus prevents the stem cell growth, the researchers found.

Related: Skin cells made 30 years younger with new 'rejuvenation' technique

Moreover, p16-carrying cells extracted from donated human lungs can also promote stem cell growth – at least in lab dishes.

This finding hints that, as seen in mice, drugs like DQ could also disrupt healing in humans.

"This combination treatment is currently in multiple clinical trials," and in general, scientists have been on the lookout for signs that senolytics disrupt healing, said Danny Roh, an assistant professor of surgery at the Boston University School of Medicine who was not involved in the study.

The new research suggests that this caution is warranted, Roh told Live Science in an email.

What this means for anti-aging drugs

While senolytics have been shown to mess with healing in the lungs and skin, some labs have found that the drugs speed up healing in fractured bones. So what gives?

"Is bone different from lung and skin? Possibly," said Sundeep Khosla, the leader of Mayo Clinic's Osteoporosis and Bone Biology Laboratory, who oversaw one of the previous bone studies. But Khosla favors another hypothesis.

In the lung and skin studies, researchers gave the senolytics every day, but in the bone studies, there were longer breaks between doses.

This strategy may hit a therapeutic sweet spot, "where there's enough inflammation for repair but not too much where you're actually starting to see negative effects," Khosla said.

"In terms of clinical development of therapeutics, the devil is going to be in the dosing," he said.

The study also raises questions about what types of zombie cells senolytics target best, Khosla added.

Senescence is more like a dial than an on-off switch, so zombie cells sit on a spectrum from least to most senescent, Peng said.

Zombies in aged mice seem especially inflammatory, and Peng and his colleagues are now investigating how that might affect healing.

Related content:

- Mini-brains show how common drug freezes cell division in the womb, causing birth defects

- Natural rates of aging are fixed, study suggests

- Scientists discover 4 distinct patterns of aging

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.