We're another step closer to reducing the need for round-the-clock insulin injections to manage diabetes after a new study showed how insulin-producing cells could be regenerated in the pancreas.

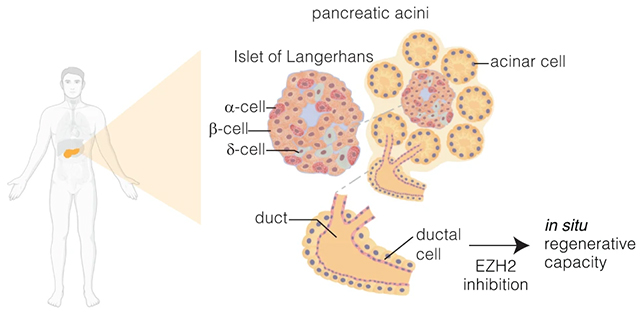

The breakthrough was made by getting pancreatic ductal progenitor cells – that give rise to the tissues lining the pancreas's ducts – to develop to mimic the function of the β-cells that are usually ineffective or missing in people with type 1 diabetes.

Researchers, led by a team from the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Australia, investigated a new use for drugs already approved by the FDA that target the EZH2 enzyme in human tissue. Ordinarily, this enzyme controls cell development, providing an important biological check on growth.

Here, two small molecule inhibitors called GSK126 and Tazemetostat – already approved for use in cancer treatments – were used to take off some of the brakes imposed by EZH2, allowing the progenitor ductal cells to develop functions similar to those of β-cells.

"Targeting EZH2 is fundamental to β-cell regenerative potential," write the researchers in their published paper. "Reprogrammed pancreatic ductal cells exhibit insulin production and secretion in response to a physiological glucose challenge ex vivo."

Previous research had suggested that cells that give rise to the duct lining, which also help to manage stomach acidity, could be converted into something like β-cells in the right environment. Now, we've got a good idea of how to do it.

Crucially, the new cells can sense glucose levels and adjust insulin production accordingly – just like β-cells. In type 1 diabetes, which the study focuses on, the original β-cells are mistakenly destroyed by the body's immune system, which then means blood glucose and insulin must be managed with regular injections.

The tests carried out by the team showed the same reaction in tissue samples taken from two individuals with type 1 diabetes aged 7 and 61, and one aged 56 without diabetes, suggesting it can work across the generations. Another positive sign is that it took just 48 hours of stimulation before regular insulin production resumed.

Around 422 million people are thought to be living with diabetes worldwide, relying on manually checking and managing blood sugar levels. It's still early days for this research, with clinical trials still to come, but it's another potential way to coax the human body to replace the functions that diabetes takes away.

It's not the only promising avenue that scientists are exploring either; new types of drugs are in development, while researchers are also working on ways to effectively protect the original insulin-producing cells before they get wiped out.

"We consider this regenerative approach an important advance towards clinical development," says epigeneticist Sam El-Osta from the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute.

"Until now, the regenerative process has been incidental, and lacking confirmation, more importantly the epigenetic mechanisms that govern such regeneration in humans remain poorly understood."

The research has been published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.