If it were ever possible to take a flight through the extreme conditions of Neptune's atmosphere, we might experience the fascinating phenomenon of diamond rain tapping at our window.

According to a new study by an international team of researchers, such a blizzard of bling could be relatively common throughout the Universe.

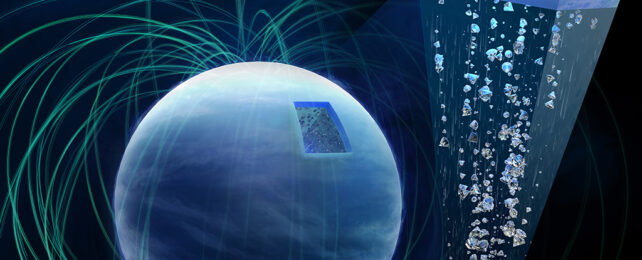

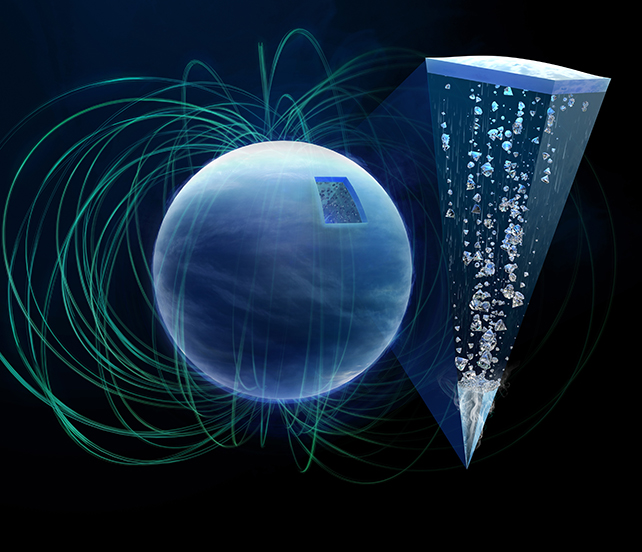

Carbon can link into a crystal on giant, icy gas planets like Neptune and Uranus because of the ultra-high temperatures and pressures deep down in the atmosphere. These conditions break up hydrocarbons like methane, allowing the carbon atoms within to connect with four others and make particles of solid diamond.

Based on the experiments outlined in the latest study, in which diamond-forming processes were simulated in lab conditions, the temperature and pressure thresholds for this kind of diamond formation are lower than scientists thought.

That would make diamond rain possible on smaller gas planets, so called 'mini-Neptunes'. There are plenty of these that we know about outside the Solar System.

These findings might also explain some mysteries about Uranus's and Neptune's magnetic fields.

"This groundbreaking discovery not only deepens our knowledge of our local icy planets, but also holds implications for understanding similar processes in exoplanets beyond our Solar System," says physicist Siegfried Glenzer from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

The team behind the new study used the European XFEL (X-Ray Free-Electron Laser) to monitor diamonds being formed from hydrocarbon compound polystyrene film, pushed to huge pressures between a vice-like setup.

This configuration allowed the team to get a longer look at the process than had been possible in previous experiments. That drawn-out examination suggested that even though intense pressure and super-hot temperatures are still very much required, they might not have to be quite as extreme as previously thought.

In terms of planets, this suggests diamonds could form at a shallower depth than scientists have been estimating – and that would then mean the descending diamond particles, dragging gas and ice along with them, might be influencing the magnetic fields of these planets in a more direct way than we've previously understood.

Unlike Earth, ice planets like Neptune and Uranus don't have symmetrical magnetic fields. That's been something of a mystery up to this point – suggesting the magnetic fields aren't formed in the planetary core – and diamonds could help explain it.

"It might kick off movements within the conductive ices found on these planets, influencing the generation of their magnetic fields," says physicist Mungo Frost, from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

This is all intriguing stuff that future studies can look into in more depth. In recent years, scientists have inched closer to understanding how this process might work on distant planets, and what the repercussions might be.

Who knows – maybe one day we'll be able to do some actual field research in the demanding atmosphere of Neptune and Uranus, enabling us to see first-hand how this diamond rain is formed.

"Diamond rain on icy planets presents us with an intriguing puzzle to solve," says Frost.

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.