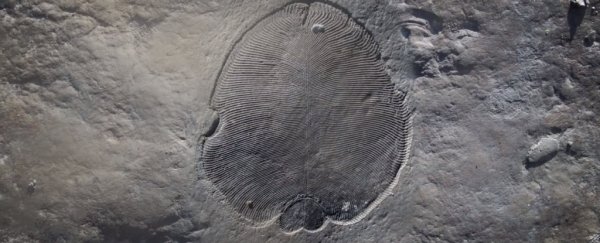

The evidence is in. A mysterious creature that lived on Earth over half a billion years ago has now been proven an animal. A fossil from 558 million years ago was so well preserved, it still had fat molecules, conclusively laying to rest the debate about Dickinsonia's identity.

Prior to the Cambrian explosion 541 million years ago, where modern animal life such as trilobites, sponges, worms and molluscs emerged, the fossil record is scant. But there was life - we have fossil evidence of a mysterious group of lifeforms known collectively as the Ediacaran biota.

The Dickinsonia genus, first described in 1947, is perhaps the most recognisable of these, and its identity has been the subject of hot debate for over 70 years.

At up to 1.4 metres (4.6 feet) in length, its flat, oval-shaped, ribbed body is unlike anything alive today.

(Ilya Bobrovskiy/ANU)

(Ilya Bobrovskiy/ANU)

Theories as to what it might be have included algae, protozoans, lichens, colonies of bacteria, jellyfish, coral, worms, a type of mushroom and coral - it has so few features in common with other organisms that the approach to categorising it has mostly been throwing ideas at the wall to see what sticks.

But the discovery of cholesterol in a Dickinsonia fossil from Russia is pretty weighty evidence in favour of the animal category.

"The fossil fat molecules that we've found prove that animals were large and abundant 558 million years ago, millions of years earlier than previously thought," said paleobiogeochemist Jochen Brock from the Australian National University (ANU).

"Scientists have been fighting for [decades] over what Dickinsonia and other bizarre fossils of the Edicaran Biota were: giant single-celled amoeba, lichen, failed experiments of evolution or the earliest animals on Earth."

The problem with a positive identification to date is that organic material degrades over time - and 558 million years is plenty of time for any clues to disintegrate.

Most recently - a year ago - Cambridge researchers identified Dickinsonia as an animal by extrapolating its growth based on the life stages of individuals, and narrowing it down to an animal. It was good research, and now there's physical evidence to support it.

But the researchers had to search hard to find this evidence. Most of the Dickinsonia fossils we have are from the Ediacara Hills in Australia, and have endured a lot of heat, pressure and weathering, the researchers said, leaving no organic matter behind.

However, some Dickinsonia fossils in Russia had retained organic matter. Except you'd have to get to these specimens, which was not easy.

"I took a helicopter to reach this very remote part of the world - home to bears and mosquitoes - where I could find Dickinsonia fossils with organic matter still intact," said biogeochemist Ilya Bobrovskiy of the ANU.

"These fossils were located in the middle of cliffs of the White Sea that are 60 to 100 metres [200 - 330 feet] high. I had to hang over the edge of a cliff on ropes and dig out huge blocks of sandstone, throw them down, wash the sandstone and repeat this process until I found the fossils I was after."

All that climbing was worth it in the end. The team sampled thin layers of organic material associated with the fossils, as well as adjacent layers of sediment to control for biomarkers that may have been distributed in the vicinity but didn't originate with the fossils.

The surrounding sediment contained carbon material associated with green algae - but the organic material from the fossils were almost exclusively cholesteroids, lipid compounds essential for the structure of animal cell membranes.

It's a result that rules out other forms of life, such as lichens and protists, since these produce different steroids, such as ergosteroids and stigmasteroids, in abundances not observed in the Dickinsonia fossils.

"Molecular fossils firmly place dickinsoniids within the animal kingdom, establishing Dickinsonia as the oldest confirmed macroscopic animals in the fossil record (558 million years ago) next to marginally younger Kimberella from Zimnie Gory (555 million years ago)," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"However alien they looked, the presence of large dickinsoniid animals, reaching 1.4 m in size, reveals that the appearance of the Ediacara biota in the fossil record is not an independent experiment in large body size but indeed a prelude to the Cambrian explosion of animal life."

The team's research has been published in the journal Science.