Evidence continues to mount against the interpretation of a cave filled with ancient hominid bones as a sacred burial ground, one used long before modern humans were burying their own dead.

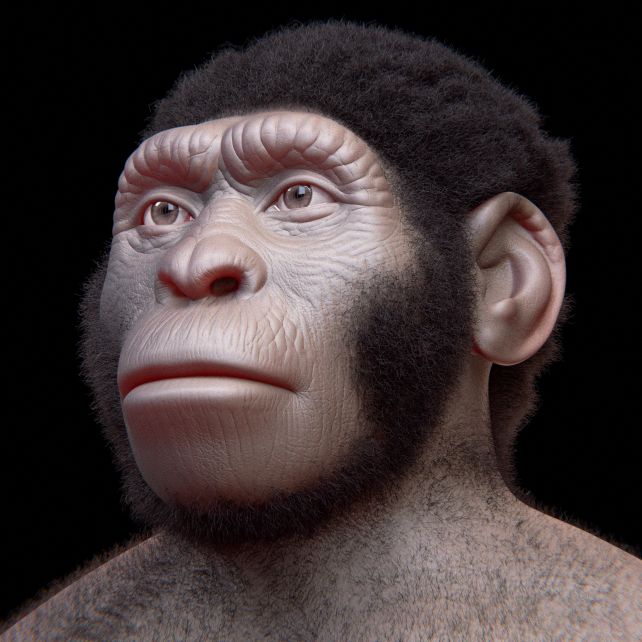

The Rising Star Cave system in South Africa contains the remains of an unusually high number of individuals of the hominid species Homo naledi that lived around 300,000 years ago, and their peculiar deposition has continued to puzzle scientists.

Then, last year, a bombshell dropped. A team led by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand published a preprint making the jaw-dropping claim that the burials were deliberate, a claim that would also be popularized through its own Netflix documentary.

If true, the finding was revolutionary. Standing at the evolutionary intersection of humans and great apes, Homo naledi was not thought to be capable of such complex acts of cognition.

Now, a new team of researchers led by anthropologist Kimberly Foecke of George Mason University has performed a new analysis of those findings, and found that the conclusions reached by Berger and his colleagues are insupportable based on the available evidence.

"We found deep structural issues with data analysis, visualization, and interpretation in addition to mischaracterization and mis-application of statistical methods in assessing data. We show that even if the data provided accurately represent the composition of the samples, when analyzed according to field standards the same data do not support the interpretations, conclusions, and claims made by the authors," Foecke and her colleagues write in their paper.

"We believe that the preprint represents an example of where data analysis has been heavily influenced by a presupposed narrative."

Berger's finding was disputed from the start. The paleoanthropologist – who is no stranger to controversy – was accused of exploiting the open publication policy of the journal eLife in which the paper appeared, which allows non-peer-reviewed papers to appear alongside peer review.

Then, after further analysis published in a peer-reviewed paper, researchers found that his cited evidence for deliberate funerary practices was highly selective, and insufficient to reach the extraordinary conclusions.

Now, Foecke and her colleagues have painstakingly gone through Berger's team's paper to tally up the evidence and reasoning behind the researchers' findings. They carefully assessed the analysis and interpretation of Berger et al. in response to their research question; they tried to replicate the experimental results Berger et al. claim to have achieved; and then, finally, they assessed whether or not the data acquisition followed established standards and best practices.

In all three areas, the researchers found, the work of Berger and his colleagues fell far short of meeting the standard necessary to support the report's conclusions.

Berger's team had analyzed soil samples in the cave, studying the chemical composition and particle size of the dirt with the reasoning that if remains in the cave had been deliberately buried, the soil on top of them would be different from the soil below.

Foecke and her team found that the paper's description of this process failed to contain important details in the soil analysis, making the method of data acquisition unclear. More importantly, Foecke and her colleagues were unable to replicate the findings. Their soil analysis did not show any significant difference between the dirt on the bodies and the dirt in the rest of the cave.

That's not to say that Homo naledi did not bury their dead. We just don't have sufficient evidence that they did, making an increasing number of scientists doubtful of claims to the contrary.

Geochemist Tebogo Makhubela of the University of Johannesburg, a member of Berger's team, agrees that some of the criticisms are fair, as he told Michael Price at Science. He says that the paper is a work in progress, and that the team is working on revisions. However, it may be reasonably argued that those revisions need to be made before a piece of research reaches the publication stage.

And it behooves us all to approach such extraordinary claims with caution.

"I hope that this work is able to instill some skepticism in the public when it comes to archaeological research in the public eye," Foecke says.

"We see so often flashy shows with charismatic archaeologists presenting huge claims about the past, but we must hold scientists who communicate with the public accountable to the science itself and ensure that we as a field are doing good work."

The findings have been published in Paleoanthropology.