If you're one of the unlucky millions of people burdened by allergies, you know that sometimes there's only so much antihistamines can do to help.

Researchers have been working to find more effective allergy treatments, and now they've discovered how a particular antibody can stop an allergic reaction from happening altogether.

An allergic reaction is the immune system's way of completely overreacting to a normally benign substance, from proteins in cat saliva to surprisingly deadly peanuts.

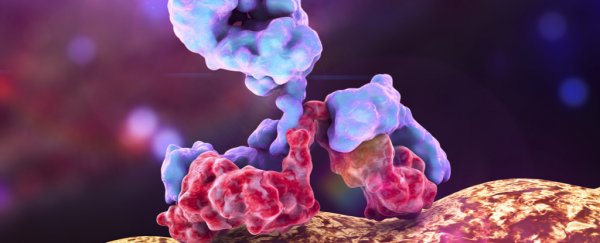

When the body is exposed to an allergen, the immune system goes into overdrive producing ridiculous amounts of a specific type of antibody called immunoglobulin E (IgE). It's a large, Y-shaped molecule that attaches itself to the immune cells tasked with releasing invader-attacking chemicals.

These compounds - especially histamine - go on to produce the varied and miserable symptoms of an allergy, whether it's a runny nose and eyes, or the more serious anaphylactic reaction that accompanies severe food allergies or insect bites.

Allergy tablets typically target these immune system compounds or their receptors, therefore preventing or at least easing the allergy symptoms. But if we target IgE itself, there's a chance to prevent the allergic reaction from even taking place.

A team led by scientists at Aarhus University in Denmark has now discovered a mechanism through which a particular anti-IgE antibody can make this miracle happen.

This new antibody, called 026 sdab, was first derived from llamas, and is akin to a range of such molecules discovered in camelid species and cartilaginous fishes.

The way 026 sdab works in the human body is by preventing IgE from getting to two specific types of immune receptors - CD23 and FceRI - and thus stopping the allergic reaction before it even starts.

"Once the IgE on immune cells can be eliminated, it doesn't matter that the body produces millions of allergen-specific IgE molecules," says senior author of the study, Edzard Spillner from Aarhus University.

"When we can remove the trigger, the allergic reaction and symptoms will not occur."

While the antibody hasn't yet been tested in actual people, the team used blood samples from people with diagnosed allergies to birch pollen and insect venom, and watched how the antibody performed.

Within just 15 minutes, treatment with 026 sdab reduced IgE levels down to 30 percent from the starting amount, and even further down when the test lasted longer.

"We can now precisely map how the antibody prevents binding of IgE to its receptors," says one of the team, molecular biologist Nick Laursen from Aarhus University.

"This allows us to envision completely new strategies for engineering medicine of the future."

There's already one anti-IgE therapy on the market, called omalizumab - it's approved in over 90 countries for the treatment of stubborn cases of allergic asthma, but isn't always effective.

According to the team, 026 sdab is a much smaller antibody than what's currently available or in development. It's also easier to produce, and is "extremely stable", which means it doesn't have to be injected like omalizumab does.

"This provides new opportunities for how the antibody can be administered to patients," says Spillner.

There's still a while to go before this amazing-sounding treatment makes its way to humans - it still needs to undergo extensive testing, including safety research.

But the team's findings could also open up avenues for discovering more similar antibodies, thus speeding up the process - and we're really excited.

"Our description of the 026 sdab mode of action is likely to accelerate the development of anti-allergy and asthma drugs in the future," the team writes in the paper.

The study has been published in Nature Communications.