Dogs can smell human stress, and a new study reveals the scent may trigger a similar emotional effect in dogs, prompting them to make 'pessimistic' decisions.

This is the first scientific evidence of human stress odors influencing emotion and learning in dogs, the UK team of researchers say, and may shed valuable new light on the ancient bond between our species.

While dogs' ability to sense human moods may come as little surprise to those who live with them, the study suggests it's stronger than many people think.

"Owners know how attuned their pets are to their emotions, but here we show that even the odor of a stressed, unfamiliar human affects a dog's emotional state, perception of rewards, and ability to learn," says senior author Nicola Rooney, a human-animal interactions researcher at the University of Bristol.

Previous studies in humans have shown we can sniff clues about other people's emotions, subconsciously detecting chemosignals in their sweat, and these hidden signals can subtly affect our own emotions and decisions.

Dogs also detect these signals from us, as other recent findings show, but Rooney and her colleagues hoped to learn how our stress odors affect them.

Since dogs are skilled at reading human verbal and non-verbal cues, the researchers decided against directly exposing them to stressed-out humans.

Instead, dogs were presented with sweat and breath samples collected from three unfamiliar human volunteers as they relaxed or did something stressful.

The relaxing activity involved watching a nature video, while the stress test involved frustrating instructions related to maths and public speaking.

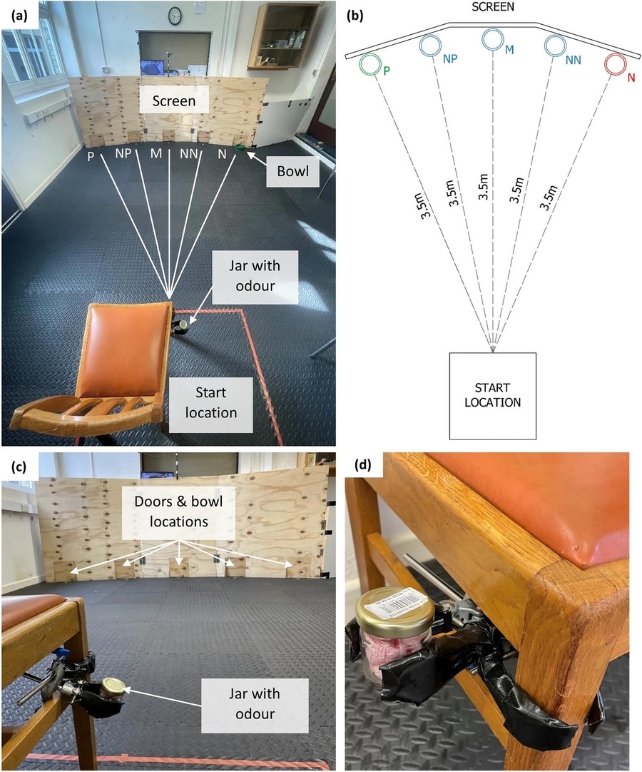

The researchers recruited 18 dog-human duos to participate in trials featuring the human odor samples. The dogs learned during training sessions that a food bowl in one location always contained a treat, while a bowl at a second site was always empty.

Dogs who learned this began to approach more quickly if a bowl was placed in the positive location P (associated with treats) than in the negative one N (associated with no treats).

The dogs' eager scurrying indicates "optimism," the team explains, or a behavioral signal hinting at an animal's emotional state, based on previous research linking people's positive and negative emotions with "optimistic" or "pessimistic" decisions, respectively.

After initial training, the researchers began to serve bowls in new places, cryptically located between the first two, to see how readily dogs approached.

They introduced three new locations, each identified by its proximity to one of the original two sites: near-positive NP, middle M, and near-negative NN.

They repeated these experiments while exposing dogs to odor samples from either stressed or relaxed humans, or to no odor at all.

Dogs were significantly less likely to approach a bowl in the near-negative position when they smelled a stressed stranger, than when exposed to the scent of a relaxed stranger or blank cloth.

The stress odor proved less discouraging when a bowl was in the middle or near-positive position, but combined with a placement near the foodless zone, the odor was apparently enough to dampen their hopes.

The same near-negative bowl location didn't seem to dissuade dogs quite as much when they weren't exposed to the stress odor. This suggests dogs were considering ambient odors along with the bowl's position to estimate the likelihood of finding food.

"Working dog handlers often describe stress traveling down the lead, but we've shown it can also travel through the air," Rooney says.

The subdued response from dogs exposed to human stress odor qualifies as pessimism, and hints at a negative emotional state. This may be adaptive, perhaps helping dogs conserve resources or avoid frustration.

Much of this dynamic is still poorly understood, and more research will be needed to clarify how exactly our odors affect the way dogs feel and learn.

And given the broad importance of dogs to humans globally – as co-workers, partners, and friends – we'd be wise to follow clues that might bolster our bond.

"Understanding how human stress affects dogs' well-being is an important consideration for dogs in kennels," says Rooney, "and when training companion dogs and dogs for working roles such as assistance dogs."

The study was published in Scientific Reports.