It's been 33 years since the Chernobyl nuclear power plant tragically blew apart in a meltdown, spreading nuclear fallout across the land. A lot has changed, but the surroundings still contain some of the most radioactive patches of soil on the planet.

Last month, researchers from the University of Bristol mapped that radioactivity in a comprehensive survey of a fraction of the exclusion zone, uncovering surprising hotspots local authorities had no idea existed.

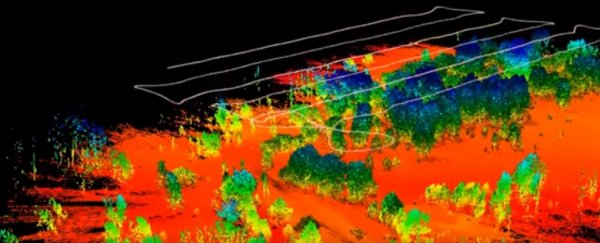

The team used two types of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) in an unprecedented fashion, mapping 15 square kilometres (5.8 square miles) of Chernobyl's 2,600 square kilometre (1,000 square miles) exclusion zone in 3D.

They used the pulsed laser system known as LIDAR to measure contours in the landscape while recording radiation levels with a lightweight gamma-ray spectrometer. A rotary-wing UAV was used to get a closer look at anything that caught their eye.

Over a period of 10 days the team sent a fixed-wing survey craft out on 50 sorties to sweep the area in a grid-pattern, starting near the relatively low-risk village of Buriakivka before making their way towards the zone's epicentre.

Using the new #DJI M600 over the Buriakivka area of #Chernobyl. Firstly a scanning LiDAR pod to generate a terrain model, followed by a gamma spectrometer to measure the radiation intensity. Had loads of fun filming from another drone too! @NCNRobotics @UOBFlightLab pic.twitter.com/xPpODC3kPD

— Kieran Wood (@DrKieranWood) April 20, 2019

One specific feature that held the researchers' interest was the 10-square-kilometre (4 square miles) Red Forest – a dense woodland of dead pine trees near the ruins of the old reactor.

The forest weathered the brunt of the station's cloud of debris, and to this day contains some of the most intense patches of radioactivity you'll find anywhere on Earth's surface.

Thanks to University of Bristol team's survey, we have a better idea of just what that means.

Amid the rusting remains of an assortment of vehicles in an old depot, radiation levels surge magnitudes beyond anything found nearby, providing any daring visitor with a year's worth of sieverts in the space of a few hours.

The hotspot's intensity might have been unexpected, but its location makes sense given the facility's role in separating contaminated soil during the disaster's clean-up.

"It's mother nature doing her job here," project leader Tom Scott told ITV science reporter Tom Clarke.

"Some of the radioactivity has died away, so the overall levels have dropped significantly. But there are certain radioisotopes present that have very long half-lives, and so they're going to be around for a long time."

Knowing exactly which areas will remain dangerous for decades to come, and which are safe to visit, will be vital for future efforts to reclaim the area.

Abandoned settlements like the nearby ghost town of Pripyat are unlikely to see new life any time soon, with Ukrainian authorities estimating it will be tens of thousands of years before the area could be declared safe for human habitation.

But that doesn't put the entire area completely off limits. Chernobyl might not be everybody's idea of a holiday hotspot, but each year around 70,000 tourists enter the exclusion zone under the careful watch of a local guide.

The site of the old station is being resurrected as a solar plant, outfitted with 3,800 photovoltaic panels to convert sunlight into a small but admirable megawatt of electricity to the local grid.

Meanwhile life scientists are paying close attention to how biology responds to both the fading wash of radiation and the sudden absence of humans.

Having highly detailed maps identifying the safest paths for entrants to follow would benefit any intrepid traveller or researcher interested in studying the aftermath of one of the biggest human-caused disasters in the modern age.