The possibility of finding some semblance of life - whether intelligent or microbial - has been a rollercoaster of emotions of late.

That 'alien megastructure' star has been one big tease (we still don't actually know wtf is up with it though), and one team of astronomers even tried to convince us that we'll never ever find aliens because they're already dead - if they existed at all. And let's not even go into the whole Fermi Paradox that's been looming over our heads this whole time.

But astronomers from Cornell University in New York have finally given us some hope, with simulations suggesting that when giant stars like our Sun start to die out, swelling to hundreds of times their original size, they could warm up frozen planets and turn them into habitable havens for life.

"When a star ages and brightens, the habitable zone moves outward and you're basically giving a second wind to a planetary system," said one of the team, Ramses M. Ramirez from the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell.

Yep - just because the moons of Jupiter and Saturn are frigid wastelands right now, doesn't mean they won't become temperate paradises 5 billion years from now when our Sun starts to head into retirement.

And that's just as well, because at the same time, Earth would become a fiery hellscape of doom, so we're going to need somewhere else to set up shop.

"Earth [will become] a sizzling wasteland," one of the team, astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger, told Calla Cofield at Space.com. "The Sun [will be] nearly at Earth's orbit. It's going to be crazy hot."

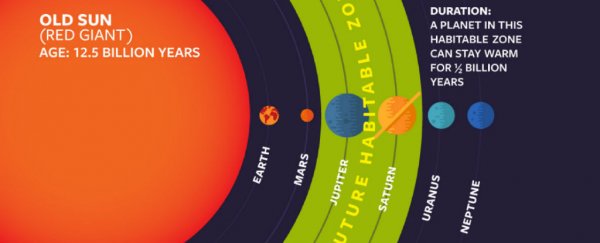

According to Kaltenegger and her team, when our Sun starts to swell up into a red giant, the habitable - or 'goldilocks' - zone of our Solar System will shift from around Earth's orbit to include the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn instead.

And while neither planet would be particularly suited for life, what with Jupiter's only signs of water floating in the clouds and Saturn being entirely made of gas, their moons could become the perfect place for primitive life to crop up as soon as temperatures begin to rise.

Carl Sagan Institute

Carl Sagan Institute

Just as thriving microbial ecosystems have been found some 800 metres beneath the west Antarctic ice sheet, living happily in frozen subglacial lakes, so too could simple organisms make their homes beneath the thick layers of surface ice on Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's moon Europa, if things heat up from their respective -198 °C (-324.4 °F) and -160 °C (-260 °F) temperatures. Some think they might already been down there.

Of course, in our Solar System, none of these changes are going to happen for literally billions of years, so that doesn't really help us much in our search for something else out there with a pulse or even just a simple genetic code. But what this research does suggest is that elsewhere in our Universe, in a solar system that has progressed to the dying stages of its sun, frozen worlds might have been brought to life.

The team points out that when astronomers are trying to narrow down the thousands upon thousands of planets beyond our Solar System as potential candidates for life, they usually look at those nearby middle-aged stars, like our Sun. But what this research suggests is they also need to be looking at systems that contain old, dying stars too, where the goldilocks zone has shifted.

"For stars that are like our Sun, but older, such thawed planets could stay warm up to half a billion years. That's no small amount of time," Ramirez says in a press release.

It's still a long shot, obviously, but the team has already identified 23 red giant stars within 100 light-years of Earth, which could be warming up new habitats for life as we speak. And even if we're still out of sync with all of this warming and cooling around the Universe, the possibility that life still has a chance - billions of years after we're all dead and gone - is pretty phenomenal to think about.

"In the far future, such worlds could become habitable around small red suns for billions of years, maybe even starting life, just like Earth," says Kaltenegger. "That makes me very optimistic for the chances for life in the long run."

The study has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal, and you can access it at pre-press website, arXiv.org.