Archeologists have discovered a collection of stud-shaped objects that wouldn't look all that out of place decorating the lips of people today. Found in the graves of a Neolithic settlement in south-east Türkiye, they could represent the earliest convincing examples of body piercing.

The site, Boncuklu Tarla, is renowned for its exceptional collection of diverse personal ornaments – more than 100,000 decorative artifacts have been found there since the settlement was first excavated in 2012.

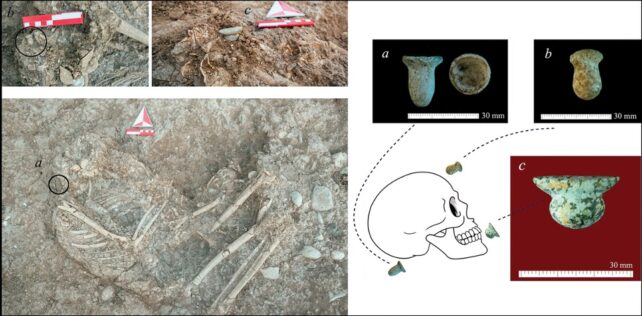

Now it lays claim to the earliest evidence of humans piercing and adorning their skin, with small plug-shaped objects found resting on or very close to the ears and jaws of grave occupants.

"These artifacts offer a unique window into the use of body perforation ornaments by the inhabitants of early sedentary communities," archaeologist Ergül Kodaş of Mardin Artuklu University in Türkiye and colleagues write in their published paper, about the discovery.

The archeological record is awash with beautiful pendants, necklaces and charms that people wore in life and death, through the Ice and Stone Ages.

Fleshy tissues such as the skin are rarely preserved, so it's less obvious if an object sat on top of the skin, or sat beneath it in some way.

Kodaş and colleagues looked at the size and shape of the objects found at Boncuklu Tarla as well as their position in the graves relative to the human remains and wear marks on the bones.

While some of the newfound ornaments had clearly moved out of place – most likely by rodents – other pieces "remained lodged in position on the upper or lower surface of the skull or under the lower jaw," the researchers report.

The jawbones of some individuals also showed signs of wear on the front side, which happens when a flat-backed stud called a labret is worn through a piercing beneath the lower lip.

Examples of jewelry pieces that look like labrets have been found dating back to 10,000 BC (about 12,000 years old), but this is the most conclusive example to date.

The earliest convincing evidence for the use of a labret in South-west Asia before this latest discovery dates to around 6,000 BC. Other artifacts found scattered across South-west Asia were inferred to be piercings based on their shape; they weren't found directly associated with the body parts through which they may have been worn.

Other compilations of past research suggest the practice of wearing piercings emerged as early as approximately 6400 BC in what is today Iran and spread through Mesopotamia. The custom later appeared in other societies throughout Africa, and Central and South America.

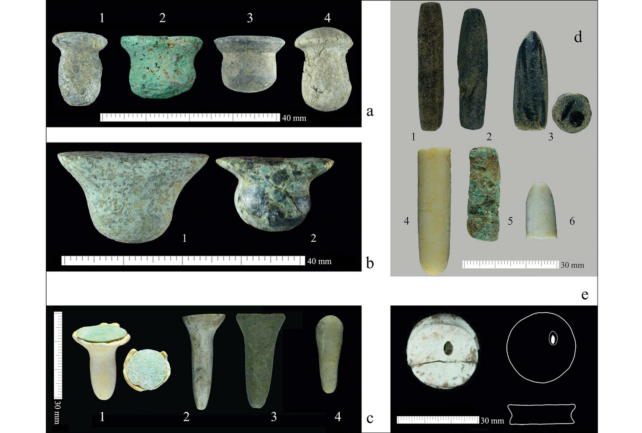

Kodaş and colleagues have so far described 85 objects found in Boncuklu Tarla graves that appear to be ornaments worn in piercings, made of materials such as limestone, flint, copper and obsidian, a volcanic glass.

These objects were found in the graves of seven male adults and nine female adults, either perched on top of or close to their skeletons. Based on the sediment layer from which they were excavated, and previous carbon dating of those sediments, five of the 85 objects date back to around 10,000 to 8000 BC, making them the earliest known examples of piercings.

No children, however, had ear ornaments or labrets near their heads. Instead, they were often buried with pendants and beads, like in other cultures.

Piercings were "probably something associated with being grown-up," archaeologist and study author Emma Baysal of Ankara University in Türkiye told CNN. "Maybe a kind of social status associated with age, or a particular role in society."

Of the seven distinct kinds of ornaments found, one type was repeatedly found beside the ears of adult grave occupants. The researchers think these nail-shaped objects, often topped with stone inlays, were likely inserted into the flesh or cartilage of the ear.

The earrings and labrets of various lengths all measured at least 7 millimeters (0.3 inches) in diameter, which would have required sizeable and likely permanent perforations of the skin, the researchers surmise.

Although only a small fraction of the thousands of beads and ornaments found at Boncuklu Tarla were designed, it seems, for ear and lip decoration, their presence shows "that the people of Boncuklu Tarla practiced ornamentation that involved the permanent adaptation of the human body in at least two areas: the ear and lower lip," the team concludes.

The study has been published in Antiquity.