An ancient skull uncovered at a 6,000-year-old megalithic monument in Spain still holds signs of what would have been a brutal ear surgery.

Archaeologists suspect the patient probably had a double-sided acute middle ear infection, which can cause earaches and fevers.

Without treatment, fluid can gather behind the eardrum, possibly causing a visible lump in the skull, hearing loss, or even life-threatening inflammation of the brain's outer membrane.

While now a common procedure, prior to the mid-19th century ear surgery was performed only in desperate attempts to save lives. Though some interpretations of ancient writings hint at surgical interventions as far back as the first century CE, solid evidence is hard to come by.

This gruesome skull discovery suggests similar procedures could have even been carried out thousands of years earlier.

The skull in this case was found at a burial site called the Dolmen of El Pendónis, which was used in the fourth millennium BCE as a resting place for bones. Those who cared for the memorial appear to have purposefully separated the heads, limbs, and pelvises of dozens of corpses in a ritualistic attempt to 'break individuality'.

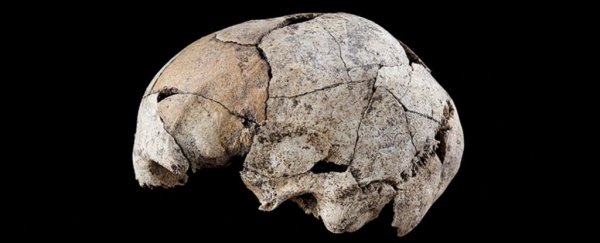

Front and side view of the skull found at the El Pendón site. (Navarro et al., Scientific Reports, 2022)

Front and side view of the skull found at the El Pendón site. (Navarro et al., Scientific Reports, 2022)

As it turns out, they did their jobs a little too well. Because the skull was found on its own, it can't tell us much about the owner. It belonged to a woman, but because there are no teeth or other limbs associated with her, it's hard to say how old she lived to be.

Based on her lack of teeth and the fusion of her skull bones, researchers think she was probably on the older side for the era, somewhere between 35 and 50.

There's also evidence she underwent some gnarly, early type of ear surgery.

Her ear infections must have been pretty bad, because without anesthetic, researchers predict a prehistoric ear surgery would have been unbearably painful.

To drill through the skull behind the ear, the woman would have needed to be held down and restrained, or given a substance that could make her less conscious of her reality.

However it happened, the surgery appears to have worked. The bones near both her ears show signs of deterioration, confirming an infection at some point, but they also show no signs of infection at the time of death. In fact, there was clear bone regeneration and remodeling, which is a common part of the healing process.

While both ears would have likely needed surgery, only her left side still shows knife marks cut in a sort of 'V' shape.

Scans of the right (a) and left (b) bones surrounding the ear. (Navarro et al., Scientific Reports, 2022)

Scans of the right (a) and left (b) bones surrounding the ear. (Navarro et al., Scientific Reports, 2022)

The fact that these marks are missing on the right side suggests these wounds had already been mended when the woman died. And that means she probably underwent excruciating ear surgery twice in her lifetime.

"Based on the differences in bone remodeling between the two temporals, it appears that the procedure was first conducted on the right ear, due to an ear pathology sufficiently alarming to require an intervention, which this prehistoric woman survived," the authors write.

"Subsequently, the left ear would have been intervened; however, it is not possible to determine whether both interventions were performed back-to-back or several months, or even years had passed. It is thus the earliest documented evidence of a surgery on both temporal bones, and, therefore, most likely, the first known radical mastoidectomy in the history of humankind."

The study was published in Scientific Reports.