Failing to achieve the Paris agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C could trigger multiple dangerous "tipping points" where changes to climate systems become self-sustaining, according to a major new study published in Science.

Even current levels of warming have already put the world at risk of five major tipping points – including the collapse of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets – but it's not too late to change course, the authors stress.

"The way I think about it is it'll change the face of the world – literally if you were looking at it from space," given long term sea-level rise, rainforest death and more, senior author Tim Lenton of the University of Exeter told AFP.

Lenton authored the first major research on tipping points in 2008.

These points are defined as a reinforcing feedback in a climate system that is so strong it becomes self-propelling at a certain threshold – meaning even if warming stopped, an ice sheet, ocean or rainforest would keep changing to a new state.

While early assessments said these would be reached in the range of 3-5 °C of warming, advances in climate observations, modeling and paleoclimate reconstructions of periods of warming in the deep past have found the thresholds much lower.

The new paper is a synthesis of more than 200 studies to produce new estimates for when common tipping points might happen.

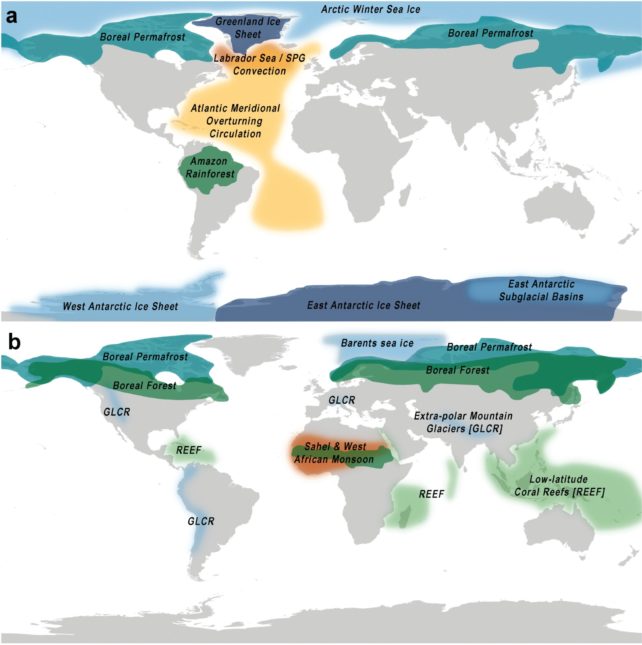

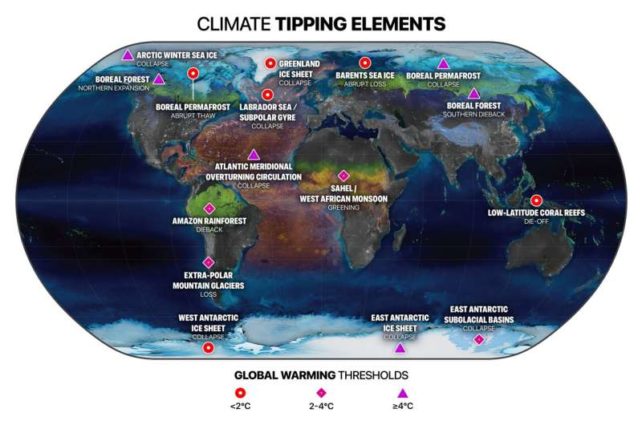

It identifies nine global "core" tipping elements contributing substantially to planetary system functioning, and seven regional tipping points, which contribute substantially to human welfare, for a total of 16.

Five of the 16 may be triggered at today's temperatures: the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets; widespread abrupt permafrost thaw; collapse of convection in the Labrador Sea; and massive die-off of tropical coral reefs.

Four of these move from "possible" events to "likely" at 1.5 °C global warming, with five more becoming possible around this level of heating.

Ten meters of sea rise

Passing the tipping points for the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets is "making a commitment eventually to an extra 10 meters of global sea level," said Lenton, though this particular change may take hundreds of years.

Coral reefs are already experiencing die-offs due to warming-induced bleaching, but at current temperatures they are also able to partly recover.

At a particular level of heating, recoveries would no longer be possible, devastating equatorial coral reefs and the 500 million people globally who depend on them.

The Labrador Sea convection is responsible for warming Europe and changes could result in much more severe winters, comparable to the "Little Ice Age" from the early 14th century through the mid-19th century.

Abrupt permafrost thaw – impacting Russia, Scandinavia, and Canada – would further amplify carbon emissions in addition to drastically altering landscapes.

Systems that may come into play around 1.5 °C also include the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, closely linked to sea levels on the US East Coast.

Starting from 2 °C, monsoon rains in West Africa and the Sahel could be severely disrupted, and the Amazon rainforest could face widespread "dieback," turning to savanna.

First author David Armstrong McKay stressed that even if the planet did hit 1.5 °C warming, much would depend on how long it stayed there, with the worst impacts coming if the temperature remained that hot for five or six decades.

Further, "these tipping points happening at 1.5° don't add a vast amount of global warming as a feedback – and that's quite important because it means we're not on a runaway train situation at 1.5 °C."

That means humanity can still control further warming, and it's "still worthwhile cutting emissions as fast as we possibly can," he added.

Lenton said what gave him hope was the idea that human society might have its own "positive" tipping points, where years of incremental change are followed by urgent, widespread action.

"That's how I can get out of bed in the morning… Can we transform ourselves and the way we live?" he said.