Every few hundred thousand years, Earth's magnetic field flips, and considering the huge impact that would have on everything from satellite systems to electrical grids, scientists are very keen to work out when the next one might be.

Hopefully it won't be for a while yet, according to the latest study – by analysing recent near-reversals of the our planet's magnetic field, researchers have concluded that we're not in line for a reversal in the near future… at least based on what's happened in the past.

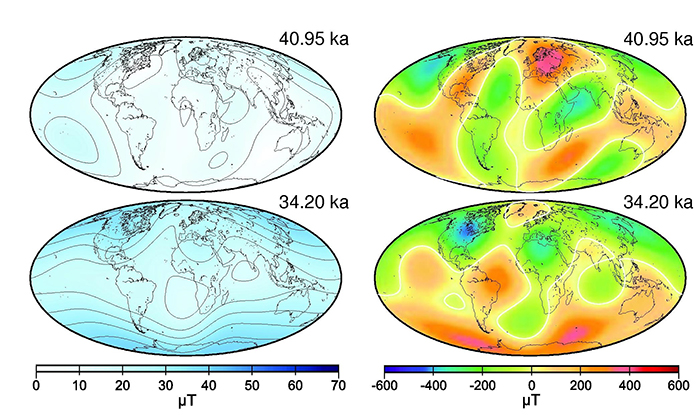

The international team of experts compared the current state of Earth's magnetic field with conditions during the Laschamp event (about 41,400 years ago) and the Mono Lake event (about 34,000 years ago). On both those previous occasions the magnetic field recovered without a flip, and the scientists think the same will happen now.

"There has been speculation that we are about to experience a magnetic polar reversal or excursion," says one of the team, Richard Holme from the University of Liverpool in the UK.

"However, by studying the two most recent excursion events, we show that neither bear resemblance to current changes in the geomagnetic field and therefore it is probably unlikely that such an event is about to happen."

"Our research suggests instead that the current weakened field will recover without such an extreme event, and therefore is unlikely to reverse."

Both the Laschamp and Mono Lake events were smaller shifts that didn't result in complete flips, as we can tell from magnetised volcanic rocks, particularly those embedded under the ocean floor.

The research matches our current magnetic field scenario with two other points at 49,000 years and 46,000 years in the past, prior to the previous events. If a complete flip didn't happen on those occasions, the hypothesis goes, then a flip isn't about to happen now either.

Analysis of the Laschamp (top) and Mono Lake (bottom) events. (PNAS)

Analysis of the Laschamp (top) and Mono Lake (bottom) events. (PNAS)

There are in fact two outcomes to look out for: a geomagnetic reversal, where magnetic north and magnetic south change places, and a geomagnetic excursion, where there are short-lived changes in the field intensity rather than the field orientation.

Both reversals and excursions can weaken Earth's magnetic field, allowing more solar radiation to hit the surface.

While this wouldn't be damaging enough to affect us (human beings have survived through past events), it could cause serious problems with satellite, communications, and power systems.

There's also the possibility it might interfere with the planet's temperature and climate, but scientists just aren't sure at the moment what the effects will be – the last full flip was 780,000 years ago, after all.

The general consensus is that these changes in Earth's magnetic field are caused by movements of molten iron and nickel deep in the planet's core. In fact, smaller fluctuations in field strength and magnetic poles are happening on a regular basis, so scientists are keen to collect as much data as possible on them.

In particular, experts are keeping an eye on the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), currently the weakest part of Earth's magnetic field. It's slowly weakening and slowly moving westward at the same time.

The more data we have, the more accurately we can predict when a reversal is likely to happen – and make sure we're ready for it.

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.