While most of us take the ground beneath our feet for granted, written within its complex layers, like pages of a book, is Earth's history. Our history.

Now researchers have found more evidence for a whole new chapter deep within Earth's past - Earth's inner core appears to have another even more inner core within it.

"Traditionally we've been taught the Earth has four main layers: the crust, the mantle, the outer core and the inner core," explained Australian National University geophysicist Joanne Stephenson.

Our knowledge of what lies beneath Earth's crust has been inferred mostly from what volcanoes have divulged and seismic waves have whispered. From these indirect observations scientists have calculated that the scorchingly hot inner core, with temperatures surpassing 5,000 degrees Celsius (9,000 Fahrenheit), makes up only one percent of Earth's total volume.

Now Stephenson and colleagues have found more evidence Earth's inner core may have two distinct layers.

"It's very exciting - and might mean we have to re-write the textbooks!" she added.

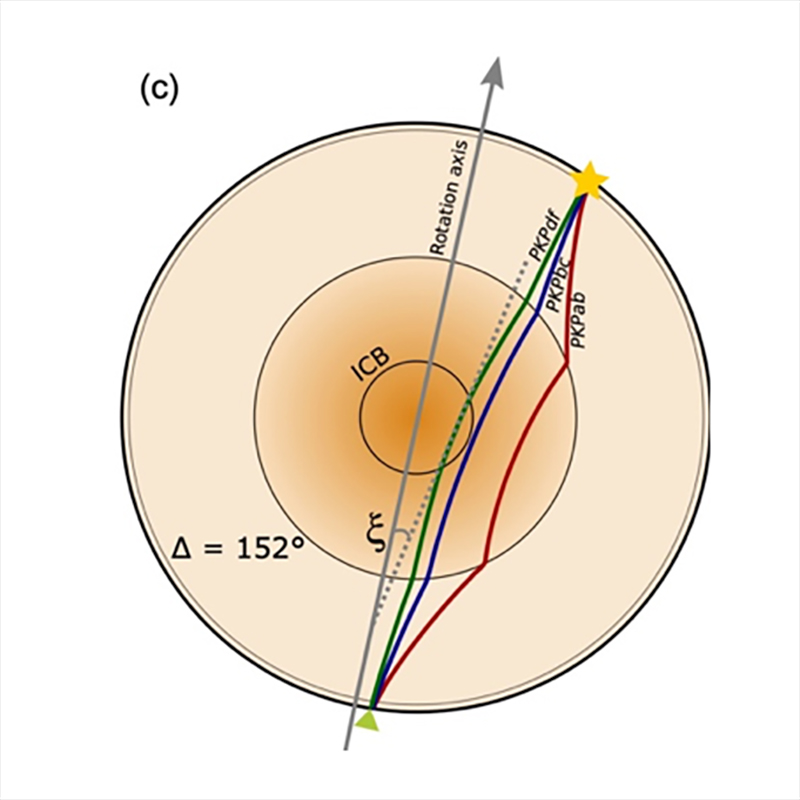

The team used a search algorithm to trawl through and match thousands of models of the inner core with observed data across many decades about how long seismic waves take to travel through Earth, gathered by the International Seismological Centre.

Differences in seismic wave paths through layers of Earth. (Stephenson et al., Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 2021)

Differences in seismic wave paths through layers of Earth. (Stephenson et al., Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 2021)

So what's down there? The team looked at some models of the inner core's anisotropy - how differences in the make-up of its material alters the properties of seismic waves - and found some were more likely than others.

While some models think the material of the inner core channels seismic waves faster parallel to the equator, others argue the mix of materials allows for faster waves more parallel to Earth's rotational axis. Even then, there's arguments about the exact degree of difference at certain angles.

This study failed to show much variation with depth in the inner core, but did find there was a change in the slow direction to a 54 degree angle, with the faster direction of waves running parallel to the axis.

"We found evidence that may indicate a change in the structure of iron, which suggests perhaps two separate cooling events in Earth's history," Stephenson said.

"The details of this big event are still a bit of a mystery, but we've added another piece of the puzzle when it comes to our knowledge of the Earths' inner core."

These new findings may explain why some experimental evidence has been inconsistent with our current models of Earth's structure.

The presence of an innermost layer has been suspected for some time now, with hints that iron crystals which compose the inner core have different structural alignments.

"We are limited by the distribution of global earthquakes and receivers, especially at polar antipodes," the team wrote in their paper, explaining the missing data decreases the certainty of their conclusions. But their conclusions align with other recent studies on the anisotropy of the innermost inner core.

A new method currently under development may soon fill in some of these data gaps and allow scientists to corroborate or contradict their findings and hopefully translate more stories written within this early layer of Earth's history.

This research was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.