The Australian summer just gone will be remembered as the moment when human-caused climate change struck hard. First came drought, then deadly bushfires, and now a bout of coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef – the third in just five years. Tragically, the 2020 bleaching is severe and the most widespread we have ever recorded.

Coral bleaching at regional scales is caused by spikes in sea temperatures during unusually hot summers. The first recorded mass bleaching event along Great Barrier Reef occurred in 1998, then the hottest year on record.

Since then we've seen four more mass bleaching events – and more temperature records broken – in 2002, 2016, 2017, and again in 2020.

This year, February had the highest monthly sea surface temperatures ever recorded on the Great Barrier Reef since the Bureau of Meteorology's records began in 1900.

Not a pretty picture

We surveyed 1,036 reefs from the air during the last two weeks in March, to measure the extent and severity of coral bleaching throughout the Great Barrier Reef region.

Two observers, from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, scored each reef visually, repeating the same procedures developed during early bleaching events.

The accuracy of the aerial scores is verified by underwater surveys on reefs that are lightly and heavily bleached. While underwater, we also measure how bleaching changes between shallow and deeper reefs.

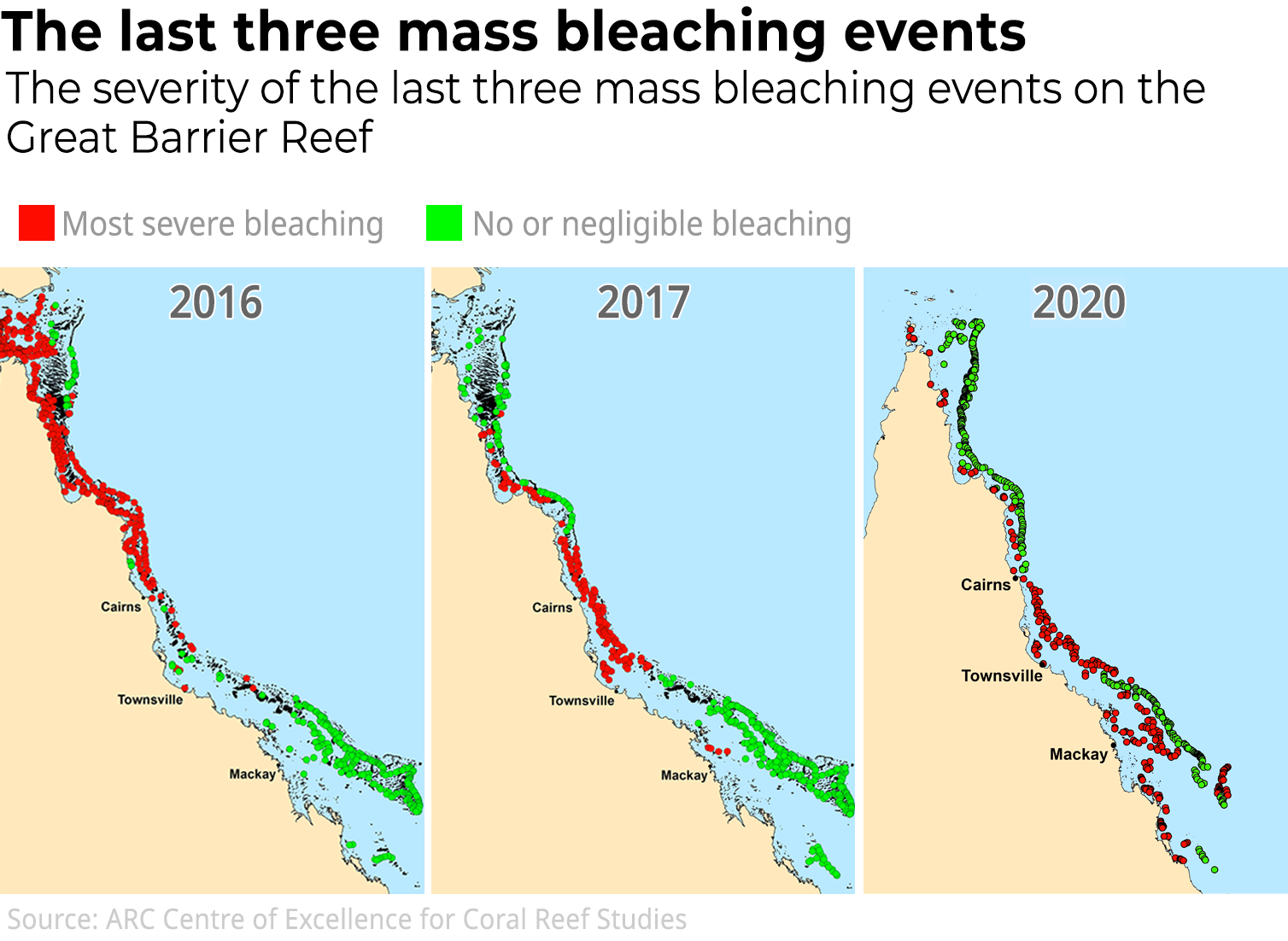

Of the reefs we surveyed from the air, 39.8 percent had little or no bleaching (the green reefs in the map). However, 25.1 percent of reefs were severely affected (red reefs) – that is, on each reef more than 60 percent of corals were bleached. A further 35 percent had more modest levels of bleaching.

ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

Bleaching isn't necessarily fatal for coral, and it affects some species more than others. A pale or lightly bleached coral typically regains its colour within a few weeks or months and survives.

But when bleaching is severe, many corals die. In 2016, half of the shallow water corals died on the northern region of the Great Barrier Reef between March and November. Later this year, we'll go underwater to assess the losses of corals during this most recent event.

Compared to the four previous bleaching events, there are fewer unbleached or lightly bleached reefs in 2020 than in 1998, 2002 and 2017, but more than in 2016.

Similarly, the proportion of severely bleached reefs in 2020 is exceeded only by 2016. By both of these metrics, 2020 is the second-worst mass bleaching event of the five experienced by the Great Barrier Reef since 1998.

The unbleached and lightly bleached (green) reefs in 2020 are predominantly offshore, mostly close to the edge of the continental shelf in the northern and southern Great Barrier Reef.

However, offshore reefs in the central region were severely bleached again. Coastal reefs are also badly bleached at almost all locations, stretching from the Torres Strait in the north to the southern boundary of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

Poor prognosis

Of the five mass bleaching events we've seen so far, only 1998 and 2016 occurred during an El Niño – a weather pattern that spurs warmer air temperatures in Australia.

But as summers grow hotter under climate change, we no longer need an El Niño to trigger mass bleaching at the scale of the Great Barrier Reef. We've already seen the first example of back-to-back bleaching, in the consecutive summers of 2016 and 2017. The gap between recurrent bleaching events is shrinking, hindering a full recovery.

After five bleaching events, the number of reefs that have escaped severe bleaching continues to dwindle. Those reefs are located offshore, in the far north and in remote parts of the south.

The Great Barrier Reef will continue to lose corals from heat stress, until global emissions of greenhouse gasses are reduced to net zero, and sea temperatures stabilise. Without urgent action to achieve this outcome, it's clear our coral reefs will not survive business-as-usual emissions. ![]()

Terry Hughes, Distinguished Professor, James Cook University and Morgan Pratchett, Professor, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.