The electromagnetic waves around Jupiter are much, much stronger around two of its moons. Around Europa, electromagnetic wave activity is 100 times stronger. And around Ganymede - the largest moon in our Solar System - it jumps to a massive 1 million times stronger.

Around planets with a magnetic field, something strange and wonderful happens. Energetic electrons become trapped in the magnetosphere, spiralling along the lines of the magnetic field, generating waves in the plasma. These waves are also responsible for auroras.

The waves can be recorded and converted into sound using radio technology. Around Earth, they sound like a cross between birdsong and whalesong. The type of wave is known as a chorus wave for this reason.

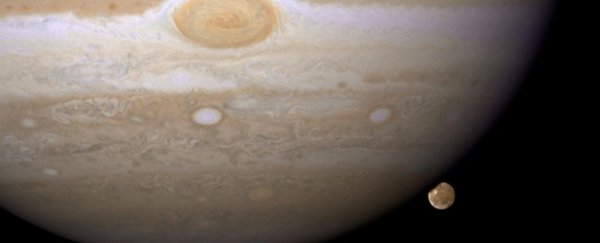

Jupiter's chorus waves are intense. The gas giant's diameter is over 11 times that of Earth, but its magnetosphere is a massive 20,000 times stronger. And, tucked inside that magnetosphere are several of its moons - including Europa and Ganymede.

Both of these moons are special. Ganymede, which is larger than Mercury, at around two-thirds the size of Mars, generates its own magnetosphere.

Europa has a magnetic field too. But it doesn't generate it alone. NASA scientists think that it's induced by an interaction between Europa's liquid ocean and Jupiter's magnetosphere.

Now, by studying data collected by Jupiter probe Galileo in the 1990s, researchers have determined that these two moons increase the strength of chorus waves.

"It's a really surprising and puzzling observation showing that a moon with a magnetic field can create such a tremendous intensification in the power of waves," said geophysicist Yuri Shprits from the University of Potsdam.

Strong plasma waves in the vicinity of Ganymede have been known about for some time. They were first detected during a Galileo flyby in 1996, and subsequently analysed by physicist Don Gurnett of the University of Iowa and his team.

What was not known was whether these plasma waves were a transient phenomenon, or a permanent feature.

Luckily, Galileo made a number of Ganymede flybys during its time around Jupiter between 1995 and 2003, and the team was able to study these data.

They found that when the probe moved past Ganymede, the electromagnetic wave activity was amplified by up to 6 orders of magnitude - 1 million times - compared to the median activity at corresponding distances from Jupiter. For Europa, the wave activity was 100 times more powerful.

These measurements were consistent across the flybys - indicating that this activity is likely permanent and ongoing.

As for why it's occurring, it can't be ruled out that the magnetospheres have absolutely nothing to do with it. However, Jupiter's moons Callisto and Io both orbit within Jupiter's magnetosphere. Neither have magnetospheres of their own, and neither produce a spike in chorus wave strength.

The science is absolutely fascinating, but it will also be useful in planning future missions. Here on Earth, chorus waves play a role in producing "killer" electrons, which can cause damage to spacecraft.

Given that the European Space Agency is planning a mission to study Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede, and that NASA is planning a Europa mission, knowing the hazards will be hugely beneficial.

"Chorus waves have been detected in space around the Earth but they are nowhere near as strong as the waves at Jupiter," said geophysicist Richard Horne of the British Antarctic Survey.

"Even if [a] small portion of these waves escapes the immediate vicinity of Ganymede, they will be capable of accelerating particles to very high energies and ultimately producing very fast electrons inside Jupiter's magnetic field."

The research has been published in the journal Nature Communications.