Around 252 million years ago, the Earth changed drastically and catastrophically. Massive, ongoing volcanic activity in Siberia wrapped the planet in a thick shroud of ash for almost a million years, killing off most of the life that was around at the time.

This event, called the Great Dying, is the most severe extinction event Earth has ever experienced (as far as we know), wiping out up to 96 percent of all marine species, and 70 percent of all terrestrial vertebrates.

The volcanic activity was so intense, it left behind an enormous region of volcanic rock, known as the Siberian Traps, or flood basalts, from the 1.5 million cubic kilometres of lava spewed out from the volcanic fissure in Earth's crust.

"The scale of this extinction was so incredible that scientists have often wondered what made the Siberian flood basalts so much more deadly than other similar eruptions," said geologist Michael Broadley of the Centre for Petrographic and Geochemical Research in France.

Now, he and his team believe they have figured it out.

The changes the world underwent during the Great Dying were dramatic. The planet warmed considerably, an effect usually attributed to the release of huge amounts of volcanic volatiles, such as carbon dioxide. It's also thought that this caused the ozone layer to thin considerably, rendering plants sterile and unable to propagate.

"Yet," the researchers wrote in their paper, "the amount of volatiles expected to be released from the Siberian flood basalts (assuming conventional plume source magmatism) is insufficient to account for the environmental degradation and climatic fluctuations that occurred during the end-Permian crisis."

So where did the extra volatiles come from?

They had been hidden inside the ground, in the outermost layer of Earth called the lithosphere, according to the team's research.

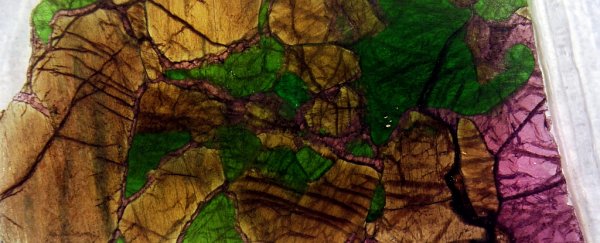

They studied pieces of peridotite rock from the mantle that had been captured and carried up to the surface by magma flows in Siberia, called xenoliths. Some of these xenoliths were from 360 million years ago, prior to the eruption, and others were from about 160 million years ago, after the event.

Analysis of these rock pieces showed something interesting. Prior to the eruption, the Siberian lithosphere appeared to be heavily loaded with a group of elements called halogens, particularly chlorine, bromine and iodine. These are present in seawater, and probably entered the lithosphere via subduction zones between the tectonic plates.

But comparison with the 160 million-year-old xenoliths showed a sharp reduction in these halogens - suggesting that something monumental had occurred to release them from the rock. Such as a huge volcanic eruption, perhaps.

Based on the team's calculations, up to 70 percent of the volatile content of the eruption's plume was extracted from the lithosphere - and this, in turn, could help account for the tremendous devastation caused by the event.

"We concluded," Broadley said, "that the large reservoir of halogens that was stored in the Siberian lithosphere was sent into the earth's atmosphere during the volcanic explosion, effectively destroying the ozone layer at the time and contributing to the mass extinction."

The study has been published in Nature Geoscience.