We all know that to have life on a world, you need three critical items: water, warmth, and food. Now add to that a factor called "entropy". It plays a role in determining if a given planet can sustain and grow complex life.

Scientist Luigi Petraccone, a chemistry researcher at the University of Naples in Italy, looked at planetary entropy. He's interested in how scientists select planets that could be habitable. He released a paper that examines something called "planetary entropy production" (PEP). Here's how it works.

A habitable world needs a biosphere with stuff living inside it. All life grows and expands, using the available water, warmth, and food resources. As it turns out, entropy plays out inside a world's biosphere. And, it needs a relatively high PEP.

That makes it more likely to have complex living systems and means it would be a good target for exploration. And, according to Petraccone's paper, it doesn't matter what the chemical basis for that life is—whether carbon, silicon, or some other element. What matters is how life proceeds to greater complexity.

What's Entropy?

Before we dive into Petraccone's paper, let's talk about entropy. The dictionary definition in physics is: "a thermodynamic quantity representing the unavailability of a system's thermal energy for conversion into mechanical work."

The second law of thermodynamics requires that the universe moves in a direction in which entropy increases.

That seems a little complex, so let's think of entropy as a measure of randomness or disorder in a system. An orderly system has exactly enough energy to do the things it needs to do.

If it produces (or gains) more energy, that gets expressed in a higher state of entropy. Living things are highly ordered and require a constant input of energy to maintain a state of low entropy.

They produce waste and by-products and, of course, lose energy as part of the process of life. The more energy coming into a system and subsequently lost by that system to its surroundings, the less ordered and more random things get. Essentially, the higher its entropy state becomes.

Entropy in biology comes into play when you look at the systems that contribute to life on a planet. Petraccone writes:

"The extent of entropy production is proportional to the ability of such systems to dissipate free energy and thus to 'live', to evolve, to grow in complexity. Generally, a certain threshold of entropy production must be exceeded for the emergence of complex self-organizing structures. Thus, the entropy production can be considered as the thermodynamic thrust that drives life emergence and evolution."

That brings us to the "planetary entropy production" (PEP) value that can help scientists target likely life-friendly planets.

The most habitable ones will be where life can generate the most entropy. The more complex and dynamic the life forms are, the more entropy they'll produce and the higher PEP value they maintain. Petraccone proposes that different planets will have more or less of an energy potential, predicting which planets are most likely to be habitable.

Applying Planetary Entropy Production to a Life Search

Figuring out where and if life happens on a planet is important. First, it needs to be within the circumstellar habitable zone (CHZ) of its star. That's where water can exist on the surface in a liquid state.

It also matters where in the CHZ the planet orbits. If it's too close to the inside edge, it may lose whatever water it has due to stellar heating (and a runaway greenhouse effect). If it's closer to the outside edge, it might not be as hospitable as one in the central area of the CHZ. In addition, a given planet may be in the perfect part of the zone but have other challenges to supporting a biosphere.

Why not search for planets throughout the CHZ? There are thermodynamic differences between the inner and outer edges of the CHZ. The inner edge is more advantageous for the development of complex biospheres.

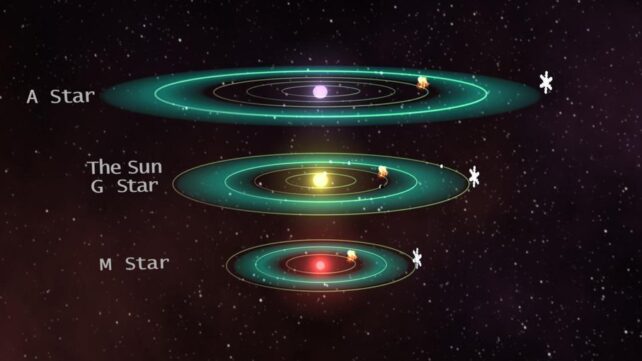

Both PEP and the available free energy for Earth-like planets increase with stellar temperature. With that information, Petraccone and his team applied their calculations to evaluate the PEP and free energy for a selected sample of proposed habitable planets.

Scientists also need to figure out the upper limit to a world's PEP value and the corresponding free energy it receives as a function of stellar temperature and planetary orbital parameters.

Petraccone writes, for example, that only Earth-like planets in the CHZ of G and F stars can have a PEP value higher than the Earth value (Earth is what we use for comparison). That means they'd be likely to support life, as opposed to planets in other parts of the habitable zone.

Why Use PEP as a Rationale for Planetary Habitability?

Interestingly, among the recently proposed habitable exoplanets, so-called "Hycean" worlds appear the thermodynamically best candidates. These are planets with liquid water oceans and hydrogen-rich atmospheres. Our planet is a good example and can be used as a "roadmap" to evaluation.

Scientists are already studying the best mix of land to oceans for a habitable world, using Earth as an analog. It lies close to the inner edge of the Sun's CHZ, which puts it in the right place to have a higher PEP value.

If we assume Earth's PEP value is required for life, then it allows planetary scientists to come up with an "entropic habitable zone" (or EHZ). It includes the distance from a star where a planet has liquid water plus a high PEP value.

Apply those criteria to planets, and it appears that worlds around low-mass stars wouldn't develop a high enough EHZ to sustain life. Nor could M and K stars. However, some fraction of worlds around F and G stars could land in the lucky "zone" and proceed to develop life.

Selecting Those Possible Habitable Planets

These days we see more and more discoveries of exoplanets around nearby stars. Examining them all to search for life is well-nigh impossible. So, scientists need some useful criteria to prioritize targets for study.

Along with other factors, entropy production seems to be a good indicator of whether or not a given world can host life—and how complex that life is.

Interestingly, a major advantage to using PEP and presence in the EHZ as a way to evaluate a world is that it doesn't require assumptions about its atmospheric condition. Nor do these factors imply any conclusions about the chemical basis of the living systems on any given world.

They simply provide a way for scientists to rate a world as they sift through thousands of exoplanets for further study.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.