The European Space Agency (ESA) has just selected the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) mission for development as one of the space agency's core missions in the coming decades.

The LISA mission is a huge deal because it would allow scientists to observe even more gravitational waves, sense their activity out to the edge of the observable universe, and discover information we aren't even sure about yet.

"We have no idea what we will discover, but perhaps we can get closer to the line that divides gravity from quantum physics. This may take us there," ESA's director of science, Alvaro Giménez Cañete, told the BBC.

Confirmed for the first time last year, but predicted by Einstein more than a century ago, gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time that emanate from the most violent and explosive events in the Universe.

As violent as they are though, we've still only been able to detect several so far and the hope is that the LISA mission would be an incredible step forward in our detection capability. LIGO detects waves between 10Hz and 1000Hz while LISA will operate in the 0.1mHz to 1Hz range.

So how will the mission work?

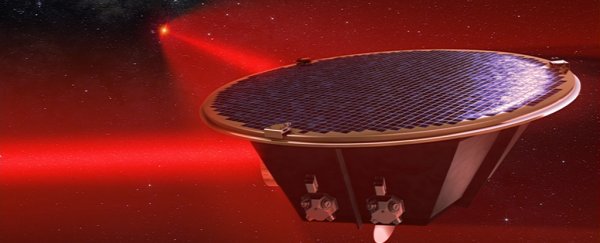

The ESA will aim to launch three identical satellites that will travel about 50 million kilometres, trailing behind the Earth.

Each satellite will be separated by 2.5 million kilometres (1.6 million miles) in a triangle pattern, and will bounce lasers between each other.

Nico 0692/Wikimedia

Nico 0692/Wikimedia

The scientists on the project will be looking at tiny movements in these light beams – hopefully detecting the slight warps of space-time caused by black holes colliding or other cataclysmic space events.

This isn't a huge surprise for those in the community – gravitational waves is pretty hot right now, and since 'gravitational universe' was identified in 2013 as the theme for this mission, LISA was looking pretty good.

"LISA looks like it's going to happen. It looks like it's on a pretty firm track," David Shoemaker, from MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics, said back in January at a meeting of the American Physical Society.

This mission has been designated as the third large-class mission in the ESA's Science Programme, but it wasn't the only exciting news at the ESA's Science Programme Committee on Tuesday.

Planetary Transits and Oscillations of stars (PLATO) has also been formally 'adopted' into the science programme, as it was selected last round in 2014.

The PLATO mission is hoping to launch in 2026 and will be able to monitor thousands of bright stars over a very large area of the sky.

The team will search for dips of light indicating that a planet is crossing in front of a star – and hopefully discovering even more Earth-like planets in the process.

The LISA pathfinder mission – a precursor to the LISA mission - has also now demonstrated key technologies needed to detect gravitational waves from space.

The LISA mission will now go into the planning stage, before hopefully being 'formally' adopted into the ESA Science Programme and launched sometime in 2034.

Basically, it's all steam ahead for the LISA mission and the ESA. We're exceptionally excited to see how this turns out.