Could a tiny planet, with weak gravity, harbor life?

A team of scientists from Harvard University say they've found the smallest possible mass a planet could be before its lack of gravitational forces would cause it to lose its atmosphere and any liquid water.

They found that the smallest possible planet that could maintain those life-enabling properties would be about 2.7 percent of the mass of Earth. That's a little more than twice the mass of the Moon and roughly half the mass of Mercury.

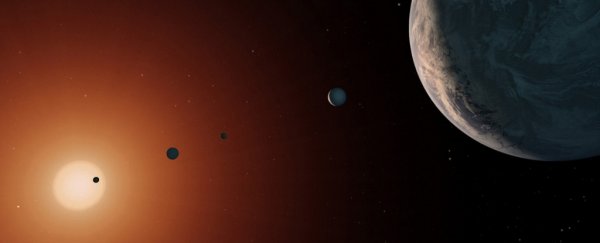

An exoplanet is said to be in a star's habitable zone if it's at the right distance to be able to support liquid water. If it's too close, it would receive too much radiation from its sun, making it too hot. Too far, and it'd be too cold for liquid water.

"When people think about the inner and outer edges of the habitable zone, they tend to only think about it spatially, meaning how close the planet is to the star," astronomer Constantin Arnscheidt, lead author of the paper describing the research, published in The Astrophysical Journal in August, told Astrobiology Magazine.

"But actually, there are many other variables to habitability, including [a planet's] mass."

If exoplanets are big enough, the researchers found there's enough of a greenhouse effect to keep them at the right temperature, regardless of their positions inside the habitable zone.

That's because the atmosphere of these relatively small planets would expand outwards thanks to relatively low gravity, which in turn would cause it to absorb more radiation from its star and thereby stabilize temperatures on its surface.

Interestingly, the research would rule out tiny ice worlds in Jupiter's orbit — they'd be too small.

These icy moons have had scientists excited about the possibility of life thanks to massive underground oceans.

But the research suggests that there could be plenty of other places we haven't discovered yet that are just the right size.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.