A pair of interlocking logs that haven't seen sunlight in half a million years could challenge some fundamental assumptions about the technology and culture of our Stone Age ancestors.

Uncovered in 2019 at the Kalambo Falls in Zambia, the objects provide archaeologists with an exceptionally rare look at wooden technology from mid-Paleolithic Africa, a time better known for an acceleration in the innovations of stone tools. The logs also predate the evolution of our own species, Homo sapiens.

An analysis conducted by an international team of researchers has now come to the astonishing conclusion that the wooden artifacts were once part of a permanent structure of some kind, such as a platform or building.

If so, the discovery complicates the conventional image of hominins as nomads hunting migrating herds or gathering seasonal flora with relatively basic tools.

"This find has changed how I think about our early ancestors," says University of Liverpool archaeologist Larry Barham, leader of a project researching Stone Age technology called Deep Roots of Humanity.

"Forget the label 'Stone Age,' look at what these people were doing: they made something new, and large, from wood. They used their intelligence, imagination, and skills to create something they'd never seen before, something that had never previously existed."

While indirect signs of woodworking by mid-Pleistocene hominins can be found in the form of plant residue or patterns of wear on stone tools, Stone Age items carved from timber rarely survive the ages.

At nearly 800 thousand years old, a solitary plank with a polished surface found in Israel is the current record holder for world's earliest prime example of carpentry.

In Africa, time wears away traces of handiwork far too readily, leaving few examples of intentionally shaped objects. Those rare examples are typically salvaged from sites with the right conditions for preserving plant materials over tens to hundreds of thousands of years.

Kalambo Falls is just such a place. Situated above a majestic 221 meter (725 foot)-high waterfall a short distance from the Kalambo River, the site saw regular flooding that deposited layers of sediment, trapping and preserving traces of archaeology between its watery layers like pressed flowers in a book.

In the mid-20th century, excavations at the site recovered notched wooden items suspected to have been carved by human hands. Dating methods suggested the items were at least 110 thousand years old, with hints that they could be far older.

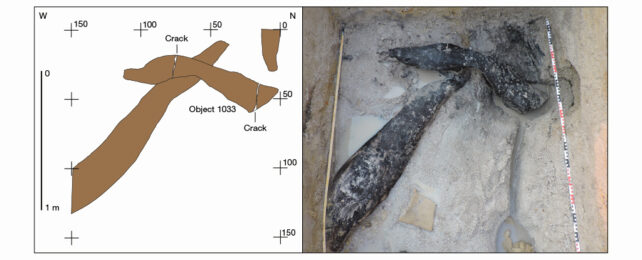

As remarkable as the objects are, few would have expected to dredge up the remains of two logs modified to lock into some form of structure.

Each of the items appears to be made from a medium-sized species of bushwillow native to the African savannah, with signs of chopping, scraping, and possibly burning around what is presumed to be an intentionally-carved notch.

The two logs, each more than a meter in length, taper to a point with clear signs of scratching and shaping.

While it's impossible to determine the purpose of the interlocking sections, viewed in association with other discoveries at the site, including several other small wooden artifacts and stone implements, the authors tentatively interpret the findings as structural.

To determine when the items may have been crafted, the researchers applied a version of infrared stimulated luminescence dating to determine when minerals called feldspar in the surrounding sediment were last bathed in sunlight.

That figure, of just under 450 to 500 thousand years ago, puts the construction well before the era in which our own species is believed to have emerged.

To take the time and effort to construct large, wooden items that can't be easily transported, we might presume the structure's makers would be relatively settled in one place, or at least frequent visitors.

"They transformed their surroundings to make life easier, even if it was only by making a platform to sit on by the river to do their daily chores. These folks were more like us than we thought," says Barham.

With its perennial waters, lush greenery, and stunning views, it's not hard to see why our ancestors kept coming back to the falls at Kalambo River since long before we were even human.

This research was published in Nature.