Something peculiar has been found inside fossilised clams from the Tamiami Formation in Florida: dozens of tiny, silica-rich glass spheres, no more than a few millimetres in size. Such beads are forged by heat, and can be created by volcanic or industrial activity - but in this case, there's one big problem.

The Tamiami Formation contains no volcanic rock, nor is it near a volcanic source. And the fossils it contains date back to the Plio-Pleistocene, between 5 million and 12,000 years ago - a long time before industry arrived on the scene.

So, what forged these beads? According to researchers, it was most likely an ancient meteorite slamming into Earth, super-heating and ejecting debris into the atmosphere where it cools and hardens into tiny glass beads called microtektites, before falling back to the ground.

If they are indeed microtektites, as several lines of analysis suggest, these spheres would be the first ever found in Florida, and maybe even the first ever found anywhere inside shell fossils.

The beads were a delightful surprise, discovered by accident. Earth scientist Mike Meyer of Harrisburg University - then an undergraduate at the University of South Florida - was prising open the fossils in search of something else entirely, namely the shells of microscopic single-celled organisms called benthic foraminifera.

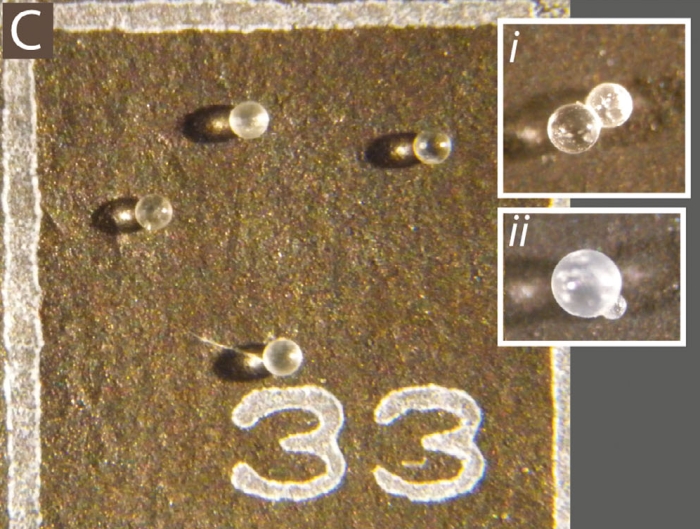

During the search, however, small glass orbs kept showing up, mostly inside southern quahog shells (Mercenaria campechiensis).

(Meyer et al., Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 2019)

(Meyer et al., Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 2019)

"They really stood out," he said. "Sand grains are kind of lumpy, potato-shaped things. But I kept finding these tiny, perfect spheres."

In all, he collected 83 of them, and just kept them sitting around in a box for more than a decade. Then he got some free time, and decided to take a closer look.

First Meyer had to mount the spheres, which is a tricky process because they're so small. This is usually done by licking a paintbrush to pick up the beads using moisture (you'd be surprised what human saliva is good for), then depositing them on a small patch of glue. "I did accidentally eat a couple of them," he said.

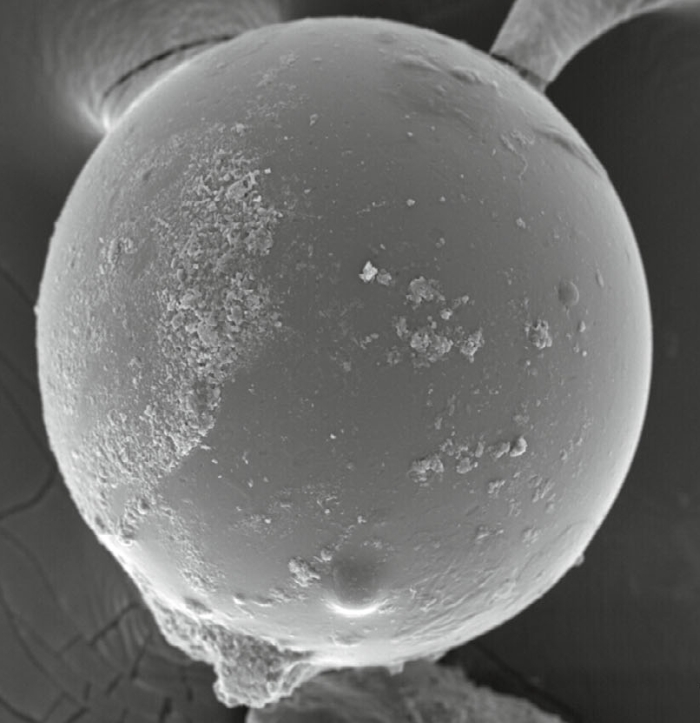

He then studied and photographed the physical properties of the spheres using optical microscopy, petrography and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with secondary electron imaging. To study their composition, he used SEM backscattered electron imaging and X-ray spectroscopy.

(Meyer et al., Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 2019)

(Meyer et al., Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 2019)

Then, he compared his results to samples of other materials, including volcanic rock, coal ash byproducts of industrial processes, and microtektites.

While it's not impossible that industrial byproducts could be in the region, they'd be unlikely to work their way into the clam fossils. Even though the shells remain slightly open for a time after the clam has died, they eventually close tightly as sediment above presses them shut, encasing whatever was trapped inside. This would have occurred at least thousands of years before humans started the first industrial activities.

Besides, the size, shape and chemical composition was unlike that of industrial coal ash particles. Nor was the composition of the particles likely to be volcanic. The two remaining options were cosmic spherule micrometeorites - tiny glass balls from space - or microtektites.

A high abundance of sodium in the balls ruled out micrometeorites, since that much of the mineral would be unlikely to survive the heating and evaporation involved in atmospheric entry.

All that left Meyer with the most likely candidate: microtektites.

Which opens another mystery in turn, because the clams were recovered from four distinct layers in the fossil bed, which means they were from four different time periods. And researchers have yet to uncover any impact sites in the region that could help them piece the history together.

"It could be that they're from a single tektite bed that got washed out over millennia or it could be evidence for numerous impacts out on the Florida Platform that we just don't know about," Meyer said.

The abundance of sodium also points to a close location for the impact: near a rock salt deposit or the ocean, both options consistent with Florida.

Sadly, the quarry where the clam fossils originated can no longer provide answers; it's been turned into a housing development. The researchers have asked fossil hunters to keep an eye out for any tiny glass beads.

The research has been published in Meteoritics and Planetary Science.