New research finds Earth's surface was first sprinkled with fresh water some 4 billion years ago, a whole 500 million years earlier than previously thought.

A team of researchers from Australia and China used isotopes of oxygen trapped in ancient minerals to determine when the first signs of fresh water may have dampened the skin of our newborn planet.

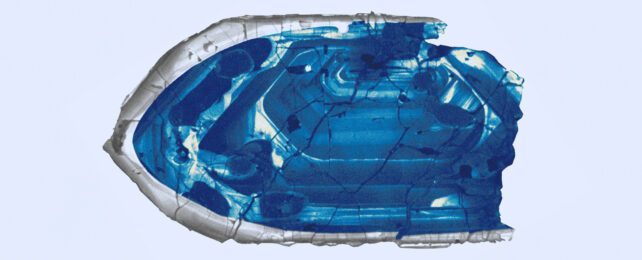

The Jack Hills in Western Australia hold the oldest surviving material from the Earth's crust. For 4.4 billion years, the primordial minerals remained relatively unchanged by heat and pressure.

The dry, red, dusty landscape doesn't get much water these days, but scientists found evidence of the Earth's oldest rains trapped inside the rock's Hadean zircon crystals, and it's a big change to our understanding of the planet's hydrological history.

"By examining the age and oxygen isotopes in tiny crystals of the mineral zircon, we found unusually light isotopic signatures as far back as four billion years ago," says geologist and lead author Hamed Gamaleldien from Curtin University in Australia.

Gamaleldien and colleagues used secondary-ion mass spectrometry to analyze the teensy grains of zircon, and deduce which oxygen isotopes were present in the magma from which the crystals formed.

The Jack Hills zircons had "extreme isotopically light" compositions only possible if they formed beneath the mantle and were also exposed to fresh water – specifically meteoric water, the kind that has recently fallen from the sky. Locked within these crystals, then, may be evidence of the Earth's first rains, penetrating into the shallows of its newly-hardened crust.

"Such light oxygen isotopes are typically the result of hot, fresh water altering rocks several kilometers below Earth's surface," says Gamaleldien.

"Evidence of fresh water this deep inside Earth challenges the existing theory that Earth was completely covered by ocean four billion years ago."

Curtin University geoscientist and coauthor Hugo Olierook points out this research has implications for many fields of science.

"This discovery not only sheds light on Earth's early history but also suggests landmasses and fresh water set the stage for life to flourish within a relatively short time frame – less than 600 million years after the planet formed," he says.

It was previously thought the crust was submerged beneath an ocean back then; some of the earliest terrestrial lifeforms we've found are 3.48 billion year old microbial reefs known as stromatolites discovered just over 800 kilometers (around 500 miles) north of the Jack Hills, in the Pilbara Craton.

But this new research suggests dry land, fresh water reservoirs, the water cycle, and possibly even life on Earth emerged much earlier than we thought.

It also reinforces the theory of a "cool early Earth" as described by University of Wisconsin–Madison geoscientist John Valley, whose 2014 paper named the Hadean zircons as Earth's oldest material.

The theory suggests that not long after the planet's sea of molten rock had congealed into a crust, Earth was cool enough to host liquid water, oceans, and a hydrosphere.

"The findings mark a significant step forward in our understanding of Earth's early history and open doors for further exploration into the origins of life," Olierook says.

This research was published in Nature Geoscience.