A Late Bronze Age grave in the archaeological site of Meggido, Israel, has presented researchers with a rare example of delicate cranial surgery that could be the earliest of its kind in the Middle East.

In 2016, archaeologists excavated a pair of tombs in the domestic section of a palace in the famous Biblical city, uncovering the remains of two individuals buried together nearly 3,500 years ago.

Now researchers from institutions in the US and Israel have published the results of an analysis of their skeletons, revealing a tragic tale of two brothers whose affluence wasn't enough to save them from an early death.

Located 130 kilometers (80 miles) north of Jerusalem, the city of Megiddo was a thriving urban center consisting of multiple palaces, fortifications, and temples. Many will know it better by its Greek name – Armageddon – prophesied as the site of the final battle before end times.

"It's hard to overstate Megiddo's cultural and economic importance in the late Bronze Age," says Tel-Aviv archeologist Israel Finkelstein, who co-authored the study on the bones.

Buried in a section of a palace thought to be reserved for the elite, amid pottery and other valuables befitting of more affluent citizens, the bodies are likely to belong to men who belonged to a powerful, if not royal, family.

A DNA analysis conducted prior to this latest investigation established their familial relationship, while hints in their size and development suggested one died in early adulthood, with the other being up to 30 years older when he passed.

Thanks to the way the bones were arranged, we know the older brother most likely outlived his sibling, with the younger's bones showing signs of having been removed and reburied.

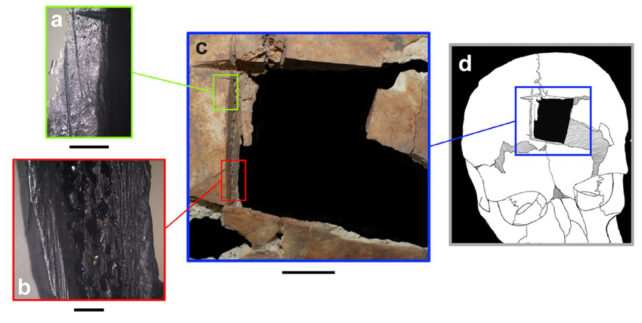

Though each of the brother's bodies display signs of illness, the skull of the older of the two clearly bears the marks of a procedure known as trepanation (also commonly referred to as trephination), which involves cutting or abrading – scraping or shaving off – bone of a living patient to expose the brain.

"You have to be in a pretty dire place to have a hole cut in your head," says lead author Rachel Kalisher, an archaeologist at Brown University in the US.

Just why the procedure was commonly performed isn't clear, with speculations ranging from the purely superstitious to relatively intuitive intentions of relieving a build-up of pressure against the brain.

In the brothers' case, whatever the intention of the surgery might have been, it was ultimately unsuccessful. The criss-cross of cut marks edging the square opening into the front of his skull showed no signs of healing, suggesting the man – considered to have been somewhere in his 20s or 30s when he died – passed away soon after his skull was cut open.

Examples of trepanation have been found in the Mesolithic records of North Africa, to Neolithic Mediterranean and central Europe. The methods are just as diverse, with examples of circular holes being drilled, square hatches being excised, and elliptical cavities being slowly abraded.

Yet there are only a few dozen other examples of trepanation across the Middle East – and none from an earlier date than these multiple millennia-old skeletons. The finding helps fill in a more global picture of how and why ancient cultures might have undertaken such a risky act of surgery.

"I'm interested in what we can learn from looking across the scientific literature at every example of trephination in antiquity, comparing and contrasting the circumstances of each person who had the surgery done," Kalisher says .

In spite of having access to affluence and influence, it's unlikely the man and his brother would have had a comfortable life. Each showed signs of sustained iron deficiency in childhood, which may have affected their development.

The older brother also had an additional line in his skull where plates met, as well as an extra molar, indicative of a rare genetic condition called cleidocranial dysplasia.

Just to add to their woes, each set of bones carried the scars of an infectious disease, most likely tuberculosis or leprosy.

It's hard to say if each individual succumbed to their infection, or even if it contributed to the need for cranial surgery. Though their lives were tragically cut short, it's clear whoever cared for them took drastic action to keep them around as long as they could.

"In antiquity, there was a lot more tolerance and a lot more care than people might think," Kalisher says.

"We have evidence literally from the time of Neanderthals that people have provided care for one another, even in challenging circumstances. I'm not trying to say it was all kumbaya – there were sex- and class-based divisions. But in the past, people were still people."

This research was published in PLoS One.