Given the abundance of moons in our own Solar System, you'd think there are heaps orbiting exoplanets, too. Such exomoons have been elusive until now - but it looks like that has finally changed.

Last year, astronomers Alex Teachey and David Kipping of Columbia University announced they'd spotted the very first exomoon candidate in data from the Kepler telescope.

Now they've conducted follow-up observations with the powerful Hubble Space Telescope. Those observations point even more strongly to the discovery of the very first exomoon.

"This would be the first case of detecting a moon outside our Solar System," Kipping said.

"If confirmed by follow-up Hubble observations, the finding could provide vital clues about the development of planetary systems and may cause experts to revisit theories of how moons form around planets."

Kepler-1625b-i, as the candidate exomoon has been named, orbits an exoplanet called Kepler-1625b, which in turn orbits a yellow, Sun-like star called Kepler-1625. The entire system is located around 8,000 light-years away, a distance recently revised with the aid of Gaia data.

The planet, Kepler-1625-b, is a Jupiter-sized gas giant, just over 11 times the radius of Earth, but with considerably more mass than Jupiter.

The candidate moon is also a whopper - according to the astronomers' calculations, it's roughly the size of Neptune, and therefore also a gas body, orbiting its planet at a distance of about 3 million kilometres.

The astronomers first got a hint of Kepler-1625b-i when they studied Kepler data on 284 exoplanets in search of an exomoon - what they describe as "little deviations and wobbles" beyond the normal transit dips in the light curve coming from the star as the planet moves across it. But it wasn't enough information.

"Kepler recorded just three transits of the planet in front of her star, and that's largely because the planet takes almost a year to complete an orbit. Three transits was tantalising, but not conclusive. Because Kepler can no longer observe the same field, we asked for some follow up observations with Hubble. Our analysis of the new light curve reveals two substantial anomalies," Kipping explained during a press briefing.

"The first is that the planet appears to transit one and a quarter hours too early; that's indicative of something gravitationally tugging on the planet. The second anomaly is an additional decrease in the star's brightness after the planetary transit has completed."

Sadly, Hubble's time is in high demand, which means the time Teachey and Kipping had with the telescope was limited to 40 hours. This time ran out before the moon's complete transit could be measured.

While these observations mount further evidence for the existence of Kepler-1625b-i, they are not, as yet, conclusive.

Other explanations for the signals observed by Teachey and Kipping could include a second planet orbiting Kepler-1625 - although, they note, so far Kepler has found no evidence of a second planet.

Another potential explanation is that one or more of the signals they observed were noise from the star itself. However, the star itself, as the team have ascertained from Kepler data, is so quiet they can't even detect its rotation. So stellar noise is possible, but Teachey and Kipping found no evidence for it.

It's reasonable to start getting excited about the possibility of a brand new discovery - a first of its kind that hopefully heralds many more in the future.

"If validated, the planet moon system, a Jupiter with a Neptune-sized moon, would be a remarkable system with unanticipated properties, in many ways echoing the unexpected discovery of hot Jupiters in the early days of planet hunting," Kipping said.

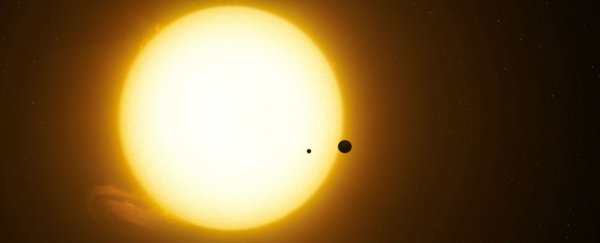

An artist's impression of exoplanet Kepelr-1625b and its moon. (Dan Durda)

An artist's impression of exoplanet Kepelr-1625b and its moon. (Dan Durda)

It will certainly raise some questions about moon formation.

Kepler-1625b-i is about 1.5 percent of the mass of the planet, similar to the mass-ratio of Earth and the Moon. But because both bodies are gaseous (which means neither are habitable as we understand it, in case you were wondering), and because of the moon's size, that raises questions about how it got there.

Our Moon may have formed as the result of a collision with Earth, but a collision with a gas planet like Kepler-1625b might not result in enough material to form a Neptune-sized moon.

Jupiter's moons are believed to have formed from a ring of material; but again, none of Jupiter's moons are the size of Neptune. Or it could have been an object that was captured by the planet's gravity from elsewhere.

For now, we can't get any answers to those questions, but we can at least hope the moon discovery will be confirmed, hopefully by future Hubble and James Webb Space Telescope Observations.

"We're looking forward to the scrutiny of the scientific community on this work and we hope we'll have an opportunity to observe the target again before too long," Teachey said.

The research has been published in the journal Science Advances.