Fitness trackers help you stay healthy by keeping count of your steps and monitoring your heart rate, driving you on to hit those cardio goals.

New research from ETH Zürich in Switzerland could see future wearable devices (with perhaps a few implants and a touch of genetic engineering) boost our health directly.

Experimental technology designed by the Swiss scientists used small pulses of electricity to trigger insulin production in test mice with specially designed human pancreatic tissues. They're calling it an 'electrogenetic' interface, and it could be used to kick target genes into action when we could use a helping hand.

"Wearable electronic devices are playing a rapidly expanding role in the acquisition of individuals' health data for personalized medical interventions," the researchers write in their published paper.

"However, wearables cannot yet directly program gene-based therapies because of the lack of a direct electrogenetic interface. Here we provide the missing link."

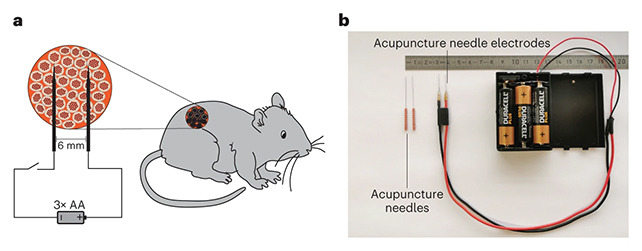

Encouraging insulin production directly could help someone with diabetes, for example. In this study, human pancreatic cells were implanted into mice with type 1 diabetes, which were then stimulated using a direct current from acupuncture needles.

It's known as the direct current (DC)-actuated regulation technology, or DART for short, and the team behind it says that it brings the digital tech of our gadgets and the analog tech of our biological bodies together.

The electricity generated non-toxic levels of reactive oxygen species, energetic molecules that – when properly managed – can start a process that activates cells engineered to respond to the change in chemistry. Changing how the cell's DNA is regulated by messing with their epigenetic 'on/off switch' molecules can potentially helping with a variety of conditions affected by genetics.

We're born with a certain set of genes, and while that genetic code remains largely unchanged during our lifetimes, the way that genes are expressed (or activated) can shift as we get older and change our habits. DART could potentially provide a means to undo some of these changes.

The researchers were able to encourage the blood sugar levels of the diabetic mice to return to normal range through this method.

Of course, we're still a long way off from a Fitbit that manages diabetes, but it's an exciting proof of concept.

One of the many challenges ahead will be getting this working in small devices. The good news is that DART requires very little power: three AA batteries would be enough to keep it running for five years, for example, with electric signals applied once per day.

The team is confident that the technology can be developed and expanded to trigger more than just insulin production. In many years to come, our health wearables could be doing much more than just reporting stats.

"We believe this technology will enable wearable electronic devices to directly program metabolic interventions," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Nature Metabolism.