An experimental vaccine that aims to slow down or prevent the progression of Alzheimer's disease has been trialed in mice with promising early results.

Mice engineered with genes that put them at greater risk of an Alzheimer's-like disease had fewer amyloid plaques following the vaccine.

They also had less brain inflammation, and showed improvement in their behavior and awareness, according to a team from Japan's Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine.

The findings are yet to be peer-reviewed, so we can't get too excited. But they've just been presented at the American Heart Association's Basic Cardiovascular Sciences Scientific Sessions 2023 in Boston.

"Our study's novel vaccine test in mice points to a potential way to prevent or modify the disease," says one of the lead researchers Chieh-Lun Hsiao, a cardiovascular biologist.

"If the vaccine could prove to be successful in humans, it would be a big step forward towards delaying disease progression or even prevention of this disease."

The announcement comes shortly after a major trial in humans found a new drug – which may soon be approved by the FDA – can help slow the disease's progression by months.

The potential new vaccine works by targeting a protein that appears in senescent cells – aging cells that have stopped dividing, but instead of being cleared away by the body they hang around and trigger inflammation.

One of the proteins senescent cells express is SAGP, or senescence-associated glycoprotein, and this is the target of the vaccine.

The researchers had developed the vaccine to treat a range of age-related diseases including Type 2 diabetes in mice.

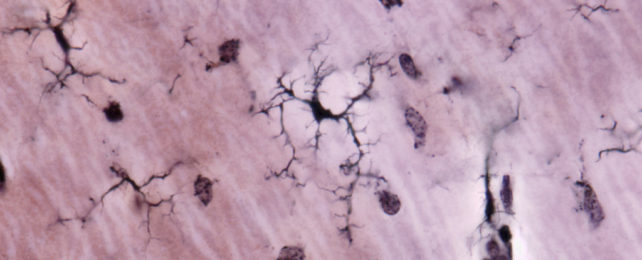

But other researchers have shown that SAGP is also highly expressed in neural support tissues (called glial cells) in people with Alzheimer's disease, so the team decided to test the vaccine in mice genetically engineered to develop a build-up of amyloid plaques and display Alzheimer's-like symptoms.

At two and four months old, these mice were either given a placebo or the SAGP vaccine.

The researchers then tested their behavior in a maze-like device at six months old, then sacrificed them so that their brains and bodies could be examined.

The mice that had been vaccinated showed significant improvements in the behavior tests. They exhibited more awareness of their surroundings and behaved like healthy mice, according to a press statement detailing the findings.

On top of that, several biomarkers of inflammation were reduced in their brains.

Vaccinated mice also had significantly reduced build-up of amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex – a region of the brain linked to language processing and problem solving.

Interestingly, the researchers found that SAGP proteins were heavily expressed near specialized brain cells called microglia. Microglia are a major part of the central nervous system's immune defense.

But microglia can also trigger inflammation – and it's already been suspected that they play a role in Alzheimer's.

The results of this trial indicate that targeting microglia could be a way to treat the disease.

"By removing microglia that are in the activation state, the inflammation in the brain may also be controlled," says Hsiao.

"A vaccine could target activated microglia and remove these toxic cells, ultimately repairing the deficits in behavior suffered in Alzheimer's disease."

This isn't the first attempt at making an Alzheimer's vaccine – there are even other potential vaccines currently being trialed in humans.

Once these findings are published, there's a very long way to go before an experimental therapy like this will be considered for trial in humans.

But it's promising that the vaccine has been linked to behavioral improvements, and it shows we might be onto something here.

"Earlier studies using different vaccines to treat Alzheimer's disease in mouse models have been successful in reducing amyloid plaque deposits and inflammatory factors," says Hsiao.

"However, what makes our study different is that our SAGP vaccine also altered the behavior of these mice for the better."

You can read the abstract presented at the American Heart Association's Basic Cardiovascular Sciences Scientific Sessions 2023 here.