There are many illnesses and injuries, including COVID-19, where the body struggles to get the amount of oxygen into the lungs necessary for survival.

In severe cases, patients are put on a ventilator, but these machines are often scarce and can cause problems of their own, including infection and injury to the lungs.

Scientists may have now found a breakthrough, and it's one that that could significantly impact how ventilators are used.

In addition to traditional mechanical ventilation, there's another technique called Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO), where blood is carried outside the body so that oxygen can be added and carbon dioxide can be removed.

Thanks to a new discovery, oxygen may now be able to be added directly, and the patient's blood can stay where it is. With a condition like refractory hypoxemia, which can be brought on by being on a ventilator, having this approach available could save lives.

"If successful, the described technology may help to avoid or decrease the incidence of ventilator-related lung injury from refractory hypoxemia," the researchers write in their new paper.

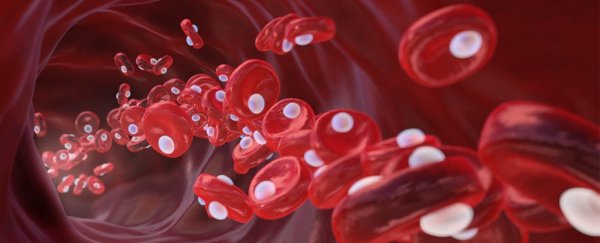

The new technique works by channeling an oxygen-laden liquid through a series of nozzles that get smaller and smaller. By the time the process is finished, the bubbles are smaller than red blood cells – and that means they can be directly injected into the bloodstream without blocking blood vessels.

A lipid membrane is used to coat the bubbles before they're added to the blood, which prevents toxicity and stops the bubbles from clumping together. After the solution is injected, the membrane dissolves and the oxygen is released.

In experiments on donated human blood, blood oxygen saturation levels could be lifted from 15 percent to over 95 percent within just a few minutes. In live rats, the process was shown to increase saturation from 20 percent to 50 percent.

"Importantly, these devices allow us to control the dosage of oxygen delivered and the volume of fluid administered, both of which are critical parameters in the management of critically ill patients," the researchers write.

The researchers are keen to emphasize that this is a "proof of concept" for now and it has yet to be tested on people. However, they seem to have found a potentially effective formula with the size of the bubbles and the coating used.

Getting oxygen into the body like this is a difficult balancing act, because complications can quickly ensue if too much or too little is added, or it's added in the wrong way. The researchers now want to test their technology on larger animals before moving on to human trials.

While it's not able to completely replace ventilators or ECMO life support in its current form, it's hoped the new device may be able to better prepare the body to be put on these machines, or keep the lungs going until a ventilator becomes available.

"It is worth mentioning that our device could potentially be integrated into existing ventilators, allowing for seamless integration into existing clinical workflows," the researchers write.

The research has been published in PNAS.