Modern-day imaging technology is able to uncover ancient buildings and structures not visible on the surface, and we just got another excellent example: the discovery of a hidden neighborhood in one of the biggest historical Maya cities.

The city in question is Tikal, now in Guatemala. Thought to have been one of the most dominant settlements in the ancient Maya empire, particularly between 200-900 CE, at its peak it could have had as many as 90,000 people living there.

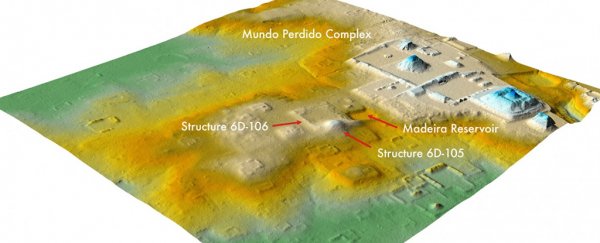

Using LIDAR scanning equipment, researchers found evidence of development under what was thought to be a natural area. What's more, the hidden ruins look to match the style of buildings in Teotihuacan – a sprawling metropolis established centuries before the rise of the Aztecs, built by a largely unknown culture.

The newly discovered structures match buildings in Teotihuacan. (Thomas Garrison/Pacunam)

The newly discovered structures match buildings in Teotihuacan. (Thomas Garrison/Pacunam)

That could give researchers some useful clues as to how these two cities interacted. Even though they were more than 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) away from each other, it's already known that traders traveled between the two urban centers.

"What we had taken to be natural hills actually were shown to be modified and conformed to the shape of the citadel – the area that was possibly the imperial palace – at Teotihuacan," says anthropologist Stephen Houston from Brown University in Rhode Island.

"Regardless of who built this smaller-scale replica and why, it shows without a doubt that there was a different level of interaction between Tikal and Teotihuacan than previously believed."

What makes the finding even more surprising is that Tikal has been extensively searched and explored since the 1950s – it's one of the ancient cities that we know most about. And all this time, there was part of it hidden from view.

Tikal is one of the most thoroughly studied archaeological sites in the world. (Stephen Houston)

Tikal is one of the most thoroughly studied archaeological sites in the world. (Stephen Houston)

Excavations were carried out after the scans to confirm the results and the presence of these buildings, with the discovery of these Teotihuacan-like structures opening up some fascinating possibilities. Tikal and Teotihuacan were different in many ways, including their overall size (Teotihuacan was much larger).

The researchers suggest that the buildings could have been a diplomatic embassy of some kind, or perhaps a military outpost. It seems to have been made by people from Teotihuacan, or locals under their control.

"It almost suggests that local builders were told to use an entirely non-local building technology while constructing this sprawling new building complex," says Houston.

"We've rarely seen evidence of anything but two-way interaction between the two civilizations, but here, we seem to be looking at foreigners who are moving aggressively into the area."

The excavations revealed that the Tikal buildings were made out of mud plaster rather than the traditional Maya limestone, suggesting some attempt to build replicas. They also matched the specific 15.5-degree east-of-north orientation of Teotihuacan's buildings.

Adding to the intrigue is the detail that Teotihuacan armies conquered Tikal in the late 4th century. It's clear that relationships ended badly between the two influential cities, but it's not certain what happened in the hundreds of years before that.

Another discovery was what looks like a burial site for a Teotihuacan warrior, matching up with similar sites in the larger metropolis over in Mexico. This is perhaps another clue as to how the two cities interacted with each other.

As well as helping historians dig deeper into the past, the new study is also an opportunity to explore one of the most discussed topics of the modern day: colonialism, and how dominant political and economic systems are felt further around the world. Meanwhile, research at Tikal continues.

"Exploring Teotihuacan's influence on Mesoamerica could be a way to explore the beginnings of colonialism and its oppressions and local collusions," says Houston.

The research has been published in Antiquity.