Nearly three in four of us will face extreme weather changes within the next two decades, a new study predicts.

"In the best case, we calculate that rapid changes will affect 1.5 billion people," says physicist Bjørn Samset from the Center for International Climate Research (CICERO) in Norway.

This lower estimate would only be reached by dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions – something that is yet to occur.

Otherwise, CICERO climate scientist Carley Iles and colleagues' modeling finds that if we continue on our current course, these dangerous changes will hit 70 percent of Earth's human population.

Their modeling also suggests that much of what's to come is already locked in.

"The only way to deal with this is to prepare for a situation with a much higher likelihood of unprecedented extreme events, already in the next one to two decades," explains Samset.

We've already lived through examples of these extremes.

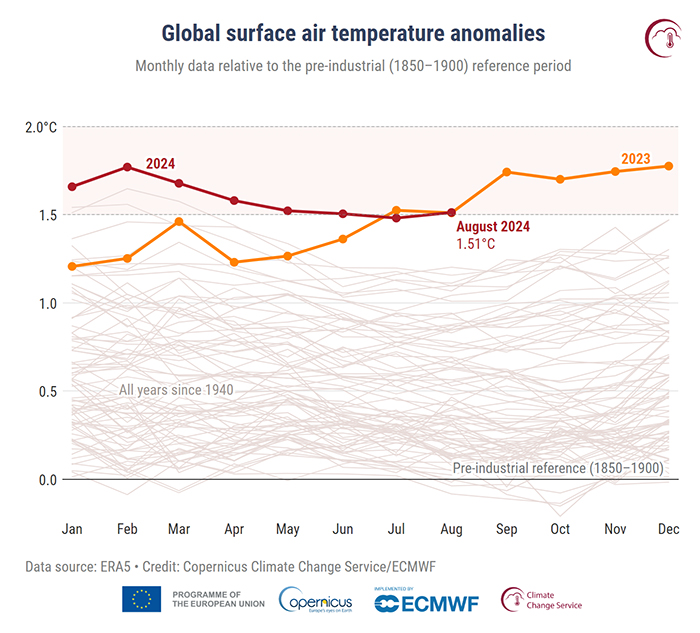

Data from Europe's climate service Copernicus shows Earth just had its hottest Northern Hemisphere summer on record. The previous record was just last year. The Southern Hemisphere has been experiencing a record-breaking warm winter too.

This global temperature increase has brought with it fatal fires, floods, storms, and droughts that are decimating crops and leading to increasingly widespread famine, creating favorable conditions for the spread of more diseases as well.

"Like people living in a war zone with the constant thumping of bombs and clatter of guns, we are becoming deaf to what should be alarm bells and air-raid sirens," Woodwell Climate Research Center climate scientist Jennifer Francis told Seth Borenstein at the Associated Press, in response to the new Copernicus data.

Iles and team's modeling suggests further extreme weather changes will occur even more rapidly than we have seen so far. This increases the chances that more dangerous extremes in temperatures, rain, and winds could occur in succession or even simultaneously.

For example, the increase in dry lightning combined with greater dry conditions is creating more frequent and intense wildfires around the world. And in 2022, a severe heatwave in Pakistan was immediately followed by unprecedented flooding, impacting millions of people.

"Society seems particularly vulnerable to high rates of change of extremes, especially when multiple hazards increase at once," the team explains in their paper.

"Heatwaves may cause heat stress and excess mortality of both people and livestock, stress to ecosystems, reduced agricultural yields, difficulties in cooling power plants, and transport disruption.

"Similarly, precipitation extremes can lead to flooding and damage to settlements, infrastructure, crops and ecosystems, increased erosion and reduced water quality."

Under our current high emissions trajectory, the tropics and subtropics in particular, where most humans call home, will face the biggest weather extremes.

"We focus on regional changes, due to their increased relevance to the experience of people and ecosystems compared with the global mean, and identify regions projected to experience substantial changes in rates of one or more extreme event indices over the coming decades," says Iles.

With drastic emissions cuts we can reduce some of these impacts, but this will cause some regions more immediate issues too.

"While cleaning the air is critical for health reasons, air pollution has also masked some of the effects of global warming," explains meteorologist Laura Wilcox from the University of Reading in England.

"Now, the necessary cleanup may combine with global warming and give very strong changes in extreme conditions over the coming decades. Rapid clean-up of air pollution, mostly over Asia, leads to accelerated co-located increases in warm extremes and influences the Asian summer monsoons."

But not acting means these worsening weather extremes will likely impact most of us within the very near future.

You can see the sorts of climate shifts expected in your home area in an interactive map here.

"These conclusions emphasize the need for both continued mitigation and adaptation to potentially unprecedented changes over the next 20 years even under a low-emissions scenario," write Iles and colleges.

This research has been published in Nature Geoscience.