When you think of eye infections, what comes to mind? Puffy, swollen bruised feeling eyelids that get glued together with gunk overnight? That feeling of having grit in your eye that can't be cleaned away? Eye infections may seem like a relatively minor – if unsightly and inconvenient – complaint, but they can also be far more serious.

Take the deadly outbreak of antibiotic resistant bacteria Burkholderia cepacia in 2023-24, for example.

Between January 2023 and February 2024, contaminated brands of lubricating eye gel were linked to the infection of at least 52 patients. One person died and at least 25 others suffered serious infections.

The outbreak has now subsided and products are back on the shelves but it isn't the first time that medicinal products have led to outbreaks of B cepacia.

The bacteria is an opportunistic pathogen known to pose a significant risk to people with cystic fibrosis, chronic lung conditions and weakened immune systems. The infection likely progresses from the mucous membranes of the eyelids to the lungs where it leads to pneumonia and septicaemia causing death in days.

But it's not just B cepacia that can threaten our health. Something as simple as rubbing our eyes can introduce pathogens leading to infection, blindness and, in the worst case, death.

Bacteria account for up to 70 percent of eye infections and globally over 6 million people have blindness or moderate visual impairment from ocular infection. Contact lens wearers are at increased risk.

The eye is a unique structure. It converts light energy to chemical and then electrical energy, which is transmitted to the brain and converted to a picture. The eye uses about 6 million cones and 120 million rods which detect colour and light.

Eye cells have no ability to regenerate so, once damaged or injured, cannot be repaired or replaced. The body tries its best to preserve the eyes by encasing them in a bony protective frame and limiting exposure having eyelids to defend against the environmental damage and ensure the eyes are kept lubricated.

Despite our bodies' best efforts to shield the eyes from harm, there are a number of common eye infections that can result from introducing potential pathogens into the eyes.

Conjunctivitis

The outer-most layer of the eye, the sclera, bears the brunt of exposure and to help protect it, it is lined by a thin moist membrane called the conjunctiva.

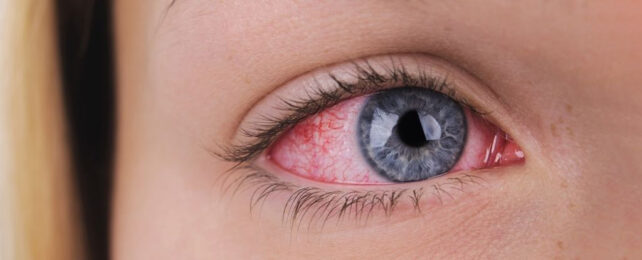

The conjunctiva is highly vascularized, which means it has lots of blood vessels. When microbes enter the eye, it is this layer that mounts an immune response causing blood vessels to dilate in the conjunctiva. This results in "pink eye", a common form of conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be caused by bacteria, allergens or viruses and typically heals by itself.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis is an inflammation of the eyelid and usually affects both sides. It can cause itchy eyes and dandruff-like flakes. It's most commonly caused by Staphylococcus bacteria, or the dysfunction of the glands of the eyelids. It can be treated by cleaning the eyes regularly.

Stye

A stye (also called hordeolum) is a painful infection of the upper or lower eyelid. Internal styes are caused by infection of an oil-producing gland inside the eyelid, whereas external styes develop at the base of the eyelash because of an infection of the hair follicle. Both are caused by bacteria, typically the S aureus form of the Staphylococcus species.

Styes can be treated by holding a clean flannel soaked in warm water against the affected eye for five to ten minutes, three or four times a day. Do not try to burst styes – this could spread the infection.

Keratitis

Keratitis is the inflammation of the cornea, the transparent part of the eye that light passes through. The cornea is part of the eye's main barrier against dirt, germs, and disease. Severe keratitis can cause ulcers, damage to the eye and even blindness.

The most common type is bacterial keratitis; however, it can also be caused by amoeba, which can migrate to other parts of the body – including the brain – and cause infection and even death.

Noninfectious keratitis is most commonly caused by wearing contact lenses for too long, especially while sleeping. This can cause scratches, dryness and soreness of the cornea, which leads to inflammation.

Uveitis

Uveitis is inflammation of the middle layer of the eye. Although relatively rare, it is a serious condition and usually results from viral infections such as herpes simplex, herpes zoster or trauma. Depending on where the inflammation is in the eye, the symptoms can be anything from redness, pain and floaters to blurred vision and partial blindness.

Exogenous endophthalmitis

This is a rare but serious infection caused by eye surgery complications, penetrating ocular trauma (being stabbed in the eye with a sharp object) or foreign bodies in the eye. Foreign bodies can be anything from dirt and dust to small projectiles such as shards of metal from drilling, explosives or soil from farm machinery and many other sources.

Dacryocystitis

Dacryocystitis is the inflammation of the nasolacrimal sac, which drains tears away from the eye into the nose. This condition can be acute, chronic or acquired at birth. Most cases are caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria.

The condition mainly affects newborns and those over 40. Seventy-five per cent of cases are women and it's most commonly found in white adults. It can lead to the stagnation of tears, creating a breeding ground for microbes.

Careful with contacts

Proper eye hygiene reduces the risk of all these conditions – and this is even more important for contact lens wearers.

Appropriate hygienic cleaning of lenses is paramount. Non-sterile water, spit and other fluids can transfer potentially dangerous microbes into the eye – a warm, moist environment that makes an ideal breeding ground for bacteria – leading to localized infection, blindness or progress to a more serious systemic infection or death.

Any persistent and painful redness or swelling of eyes should be checked by a registered health professional.![]()

Adam Taylor, Professor and Director of the Clinical Anatomy Learning Centre, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.