One of the biggest ingredients in the creation of a fossil is time. Lots and lots and lots of time - thousands to millions of years. So studying the process in action? That's a little tricky.

But now a team of researchers has figured out a way - by compressing that incredibly lengthy process into a day.

There is already an experimental approach commonly used to try and understand the fossilisation process.

It's called artificial maturation, and it does involve applying heat and pressure. It's not dissimilar to the High Pressure High Temperature method of creating synthetic diamonds.

This is an attempt to replicate what usually occurs over millions of years as a piece of organic material is buried in sediment, which applies pressure, while slow geothermal heat bakes it from inside the Earth, sometimes leaving behind a carbon impression.

However, as Field Museum palaeobiologist Evan Saitta discovered, the results of this process can be … inconsistent.

When he tried it with feathers, he ended up, not with a nice fossil, but a stinky sludge.

"What we are coming to realise is that fossils aren't simply a result of how fast they rot, but rather the molecular composition of different tissues," explained palaeobiologist Jakob Vinther of the University of Bristol.

"However, it is inherently difficult to take the conceptual leap from understanding chemical stability to understanding how tissues and organs may, or may not, survive."

The missing ingredient, Saitta thought, might be sediment. This is where fossils naturally form; the porousness of the material might allow for any stinky liquids to drain away, leaving behind a nice dry fossil.

He teamed up with Tom Kaye of the Foundation for Scientific Advancement to devise a method of creating carbonaceous fossils out of current plant and animal specimens.

They took samples from modern day lizards, bird feathers, leaves and resin, and for the first time used a hydraulic press to tightly compress them into small tablets of sediment, about 19 millimetres (0.75 inches) in diameter.

These were then placed in a seal metal tube, and heated in a laboratory oven at a temperature of about 483 Kelvin (210 Celsius or 410 Fahrenheit), while maintaining a pressure of around 240 bar (3,500 psi). This part was already established for artificial maturation.

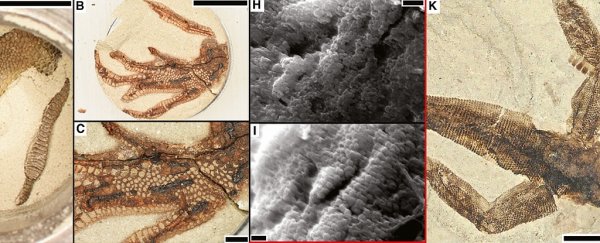

(Saita et al./Palaeontology)

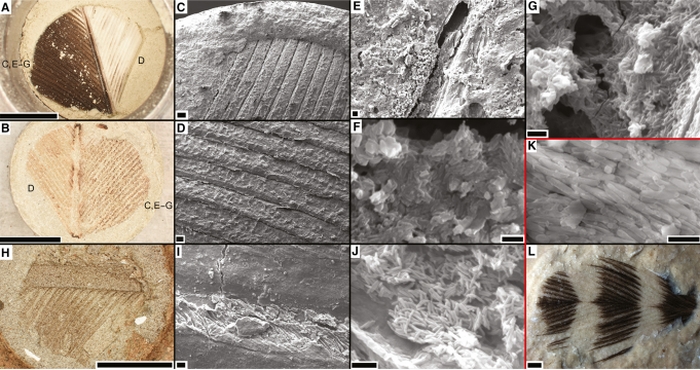

(Saita et al./Palaeontology)

The resulting fossils were spectacularly well preserved.

"We were absolutely thrilled," Saitta said. "We kept arguing over who would get to split open the tablets to reveal the specimens. They looked like real fossils - there were dark films of skin and scales, the bones became browned. Even by eye, they looked right."

You can see for yourself in the images above.

At the top of the page, images B, C H and I are all from the "synthetic" fossil. K is from a fossilised lizard dating back to the Eocene.

And in the feather image above, only K and L are "real" fossils, dating back to the Early Cretaceous.

They held up to scrutiny under the electron microscope, too: just like in real fossils, the films were made up of melanosomes, the organelle found in animal cells that produces and stores the pigment melanin, which gives animals their colour.

And, just as real fossils don't contain proteins and fatty tissue, neither did the lab-created fossils.

The researchers' new ingredient - the clay - had allowed those unstable biomolecules to leak out into the sediment, instead of turning the entire fossil to mush.

This could be invaluable. Fossils that preserve bits of bone or shell - sometimes via permineralisation or casting - are common, but carbonaceous fossils, which preserve tissue such as skin and feathers, can tell us a lot about how animals evolved.

"The approach we use to simulate fossilisation saves us from having to run a seventy-million-year-long experiment," Saitta said.

"Our experimental method is like a cheat sheet. If we use this to find out what kinds of biomolecules can withstand the pressure and heat of fossilisation, then we know what to look for in real fossils."

Also hands up if you want to see a new industry for fossilising dead pet lizards?

The team's research has been published in the journal Palaeontology.