Scientists are predicting a worldwide fall in family sizes before the end of the century, as families get more 'vertical' – meaning more grandparents and great-grandparents, and fewer cousins, nieces, and nephews.

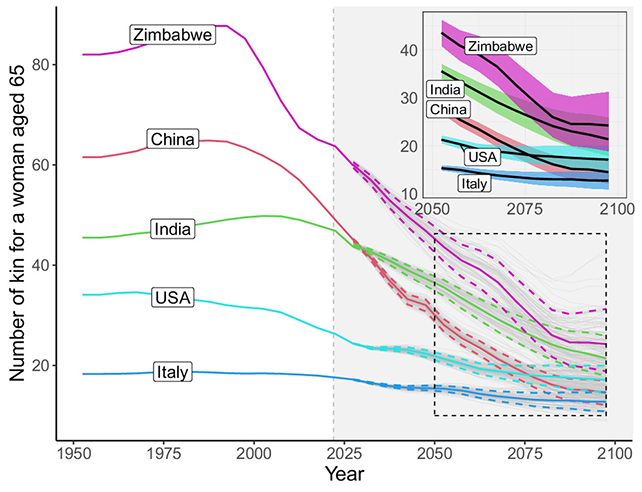

In a new study by an international team of researchers, mathematical models were used alongside existing population records and projections to calculate an average drop in family size of 35 percent by 2095.

The reduction will vary from country to country – as families in some nations are typically much larger than those in others – but taken as a whole, the research team says it highlights how the family support network is going to shift over the coming decades.

"We asked ourselves how demographic change will affect the endowment of kinship in the future," says social scientist Diego Alburez-Gutierrez from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Germany.

"What was the size, structure, and age distribution of families in the past, and how will they evolve in the future?"

While the study doesn't delve too deeply into the reasons behind the projected decline in family sizes, it does point to an overall drop in mortality rates at older and younger ages.

As mortality rates drop, it can contribute to changes in societal norms, economic factors, and family planning practices. That trend then leads to fewer siblings in each generation.

Add in the shift we're seeing towards couples having fewer children and having children later in life, and you can see why the kids of today aren't having as many brothers and sisters as the kids in previous generations. That then affects the numbers of cousins, nephews, and nieces – the extended family.

At the same time, we're all living longer, generally speaking – meaning a bigger gap between the youngest and oldest members of a family. Elderly family members can't necessarily offer care and support though, and may in fact need it themselves.

"Our findings confirm that the availability of kinship resources is declining worldwide," says Alburez-Gutierrez. "As the age gap between individuals and their relatives widens, people will have family networks that are not just smaller, but also older."

As these "kinship resources" become stretched, families may need more support from outside. The researchers compare a typical 65-year-old woman in 1950, who would've had an average of 41 living relatives, with a typical 65-year-old woman living in 2095 – who is expected to have just 25 living relatives.

Some 1,000 kinship histories for each country were analyzed for the study, based on United Nations data. If the projections turn out to be right, the shift towards more 'vertical' families is going to have consequences for family dynamics, and for the societies that support them.

"These seismic shifts in family structure will bring about important societal challenges that policymakers in the global North and South should consider," says Alburez-Gutierrez.

The research has been published in PNAS.