The idea came to him in a dream, he later claimed, a vision delivered by supernatural forces.

It was 1941, and Rudolf Hess – the Deputy Führer and second-in-line to Hitler himself – embarked upon a perilous solo flight to Britain in a wild bid to broker peace with Germany's bitter enemy. Or did he?

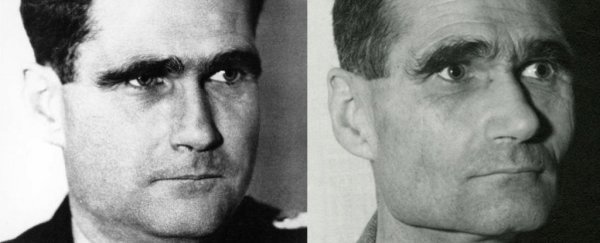

Was the man (who was later captured) actually Rudolf Hess, or, as a 70-year-old conspiracy theory would have you believe, an indistinguishable impostor: somebody sent to fool the allies for some nefarious Nazi purpose, or even a lookalike planted by the Brits?

None less than Franklin Roosevelt himself believed the doppelgänger theory to be true, and for decades, rumours have swirled around the incident, described in a new study as a "bizarre defection… one of the most mysterious episodes of World War II".

Ruse or not, the mission failed. Hess – or his supposed lookalike – made it to Scotland, but was caught immediately while struggling with his parachute.

He was a prisoner for the rest of his days, eventually receiving a life sentence at the Nuremberg Trials. He spent his last four decades at Spandau Prison in West Berlin, where he was found dead in 1987 at the age of 93, in an apparent suicide.

The later cremation of Hess's remains made it seemingly impossible to ever know for sure whether the prisoner known as 'Spandau #7' was a doppelgänger or the actual Deputy Führer he claimed to be – a close personal friend of Hitler, and the 16th member of the Nazi Party.

Without physical remains to examine, numerous points of evidence supposedly bolstering the conspiracy theory could not be examined, meaning the hypothesis could be neither proved, nor disproved.

For instance, Spandau #7 supposedly lacked chest scars consistent with Hess's WWI bullet wound, and didn't have Hess's gap in his front teeth. The prisoner also unusually refused to see family visitors, and claimed a mysterious case of amnesia.

Against all the odds, however, one final, crucial piece of the Hess puzzle yet remained in play.

Decades after Spandau #7's death, researchers made the accidental discovery that a blood sample taken of the prisoner in 1982 still existed – and was stored at Walter Reed Army Medical Centre in Washington DC.

"I first became aware of the existence of the Hess blood smear from a chance remark during my pathology residency at Walter Reed," first author and retired US Army pathologist Sherman McCall told New Scientist.

"I only became aware of the historical controversy a few years later."

With the sample in tow, McCall and his team tracked down one of Hess's living male relatives (who remains anonymous), and compared DNA markers between the blood smear and a sample of the relative's volunteered saliva, not knowing what they would find.

"No match would have supported the impostor theory, but finally we got a match," senior researcher Jan Cemper-Kiesslich from the University of Salzburg in Austria explained to The Guardian.

According to the researchers, the DNA analysis indicates there is a greater than 99.99 percent chance that Spandau #7 was in fact Rudolf Hess.

For the team – and hopefully for the rest of us, too – that's enough to consider this decades-old mystery finally solved.

"Due to the lucky event of the presence of a biological trace sample originating from prisoner 'Spandau #7', the authors got the unique chance to shed new light on one of the most persistent historical memes of World War II history," the team write in their paper.

"The conspiracy theory claiming that prisoner 'Spandau #7' was an impostor is extremely unlikely and therefore disproved."

The findings are reported in Forensic Science International: Genetics.